Washington’s Farewell Address (1796)

Overview: When George Washington decided not to run for a third term in 1796, he did so with full recognition that history was watching. Washington used his carefully crafted Farewell Address to share lessons and insights drawn from nearly a half century of public service. Washington framed his address as the “disinterested warnings of a parting friend” who was stepping down and was now free of “personal motive” that might “bias his counsel.”

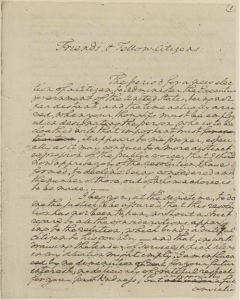

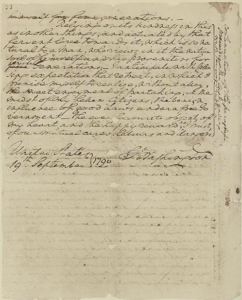

Washington’s farewell remarks were presented as an open letter addressed to “The People of the United States of America,” his “Friends and Fellow Citizens.” Reflecting his modesty, Washington signed the letter simply as G. Washington. The day that it was published Washington left Philadelphia for Mount Vernon.

Distilled to its core, the 7,641 word address was a call for national unity at home and independence abroad. Washington assailed excessive partisanship based on ideological or sectional agendas. According to Washington, “unity of government which constitutes you one people” was subject to attack by both “internal and external enemies.”

For Washington, the corollary to national unity and patriotism at home was neutrality in foreign relations. Washington urged Americans to subordinate their minor differences to the larger national interest. Washington wished that the “union and brotherly affection may be perpetual; that the free Constitution, which is the work of your hands, may be sacredly maintained….”

Washington began drafting the address in 1792 when he was first considering retirement after one term. Washington filed away the draft after his cabinet unanimously prevailed upon him to serve a second term. Ultimately the address went through multiple drafts at the hands of two of the most brilliant political minds in American history, who helped Washington distill his wisdom for succeeding generations.

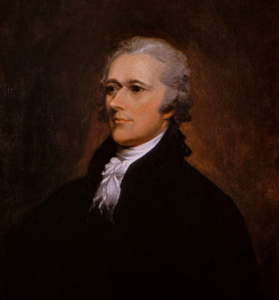

Originally, Washington worked with James Madison on the early draft. Four years later Washington called on Alexander Hamilton to help revise and finalize the address. It is generally agreed by historians that the language and argument are Hamilton’s but the underlying ideas are essentially Washington’s. Joseph Ellis answers the perennial question of the authorship of the Farewell Address by concluding that, “it was a collaborative effort in which Hamilton was the draftsman who wrote most of the words, while Washington was the author whose ideas prevailed throughout.”

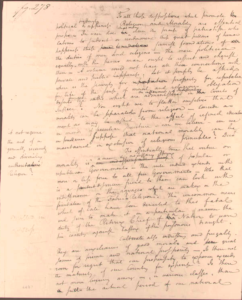

Copied below are the first and last pages of Washington’s 32 page final handwritten copy which is held by the New York Public Library.

As described by historian Ron Chernow in his biography of Alexander Hamilton, “[t]here was piquant irony in Washington asking Hamilton – who had espoused a perpetual president at the Constitutional Convention – to draft the farewell address. Hamilton would now help to embed in American politics a tradition of presidents leaving office after a maximum of two years, a precedent that remained unbroken until Franklin Roosevelt.”

Publication of the address: At a time when the nation’s capital was temporarily located in Philadelphia, Washington decided that the address was properly published in Philadelphia’s largest paper, Claypoole’s American Daily Advertiser. Washington personally delivered the 32-page handwritten address to the publisher, who immediately understood the gravity of the assignment.

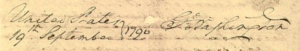

Historians suggest that Washington dated the letter September 17, to coincide with the 9th anniversary of the adoption of the first draft of the Constitution. On September 19, 1796 the letter was published under the simple title “The Address of General Washington To The People of The United States on his declining of the Presidency of the United States.”

The address was immediately reprinted in every major newspaper across the country. It fell, however, to the Courier of New Hampshire to label the address with the unmistakeable title that it would become known for, “Washington’s Farewell Address.”

While it has become a Senate tradition to annually read aloud the Farewell Address on Washington’s birthday, it is a misnomer to call it an address, since Washington never delivered it as a speech. More recently, the Farewell Address has been reintroduced to new generations of Americans by Lin-Manuel’s song, One Last Time, in the Hamilton musical. Links to YouTube videos of the song are set forth at the bottom of this post.

Due to its size, publishers of smaller formatted newspapers could not fit the entire address in a single newspaper. Some newspapers subdivided the address into two installments. Others resisted doing so to avoid showing disrespect to Washington or detracting from the force of his message. Many newspapers realized that there was profit to be made and reprinted the address in pamphlet form.

Because Washington did not put a title on the letter, newspapers had to decide how to describe it. For example, New York printer James Oram titled his pamphlet, Resignation of His Excellency George Washington with the heading The Disinterested Warnings of a Parting Friend. In Boston, printer John Russell titled the pamphlet The Legacy of the Father of His Country. For a discussion of the contemporaneous printings of the Farewell Address a good source is George Washington, A Life in Books by Kevin Hayes.

Washington’s unique role in American history: Without equal, George Washington was the central thread that tied together early American history. Beginning with the Revolutionary era and continuing through the formative years of the newly created United States, Washington was regularly toasted as the “man who unites all hearts.” The indispensable father of the new nation was eulogized in 1799 by General Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee, as the “First in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen.”

Washington was the highest ranking American military commander during the French and Indian War. Prior to the Revolutionary War, he was a strong supporter of colonial rights and co-wrote the Fairfax Resolutions calling for a Continental Convention. For eight years he served as the commander-in-chief of the Continental Army. In 1787 he presided over the Constitutional Convention. He was the unanimous choice of the Electoral College to be the first president in 1788 and was unanimously re-elected in 1792.

As described by Joseph Ellis, Washington was “the American Zeus, Moses and Cincinnatus all rolled into one.” In the book His Excellency George Washington, Ellis explained that “No American had ever before enjoyed such transcendent status. And over the next 200 years of American history, no public figure would ever reach the same historic heights.”

Washington’s “Vine and Fig Tree”: Over the years Washington had spoken of his desire to retire under his own “vine and fig tree” at Mount Vernon. Washington borrowed the image from the prophet Micah, who looked forward to the day when swords would be beaten into plowshares and nations would no longer take up sword against nation. After the bitter battle over Jay’s Treaty Washington was emotionally wounded. “What no British bullet could do in the revolutionary war, the opposition press had managed to do in the political battles of his second term” writes Joseph Ellis in Founding Brothers. Click here for a discussion of the heated partisan battle over Jay’s Treaty.

The Address builds on the fatherly advice that Washington provided thirteen years earlier at the conclusion of the Revolutionary War in his June 8, 1783 Circular Letter to the States. Washington wrote his Circular Letter in connection with his resignation as Commander and Chief of the Continental Army. Little did Washington know as he returned to “domestic retirement” that his work was far from over. Four years later he would be called upon to preside over the Constitutional Convention in 1787 and become President in 1789. In the 1783 Circular, Washington spoke of spending the rest of his life in a state of “undisturbed repose,” but his “vine and fig tree” would have to wait until 1796.

Contents of the Farewell Address: The very first paragraph of the Farewell Address alerted the nation that Washington was not going to be running for a third term. “It appears to me proper..that I should now apprize you of the resolution I have formed, to decline being considered among the number of those out of whom a choice is to be made.”

Washington advises the he had hoped to retire earlier, prior to the last election, and had even prepared a farewell address, “but mature reflection on the then perplexed and critical posture of our affairs with foreign nations, and the unanimous advice of persons entitled to my confidence impelled me to abandon the idea.”

In the address Washington warned against the baneful effects of partisan spirit and geographical distinctions. In foreign affairs, he advised against long-term alliances with foreign nations.

The common and continual mischiefs of the spirit of party are sufficient to make it the interest and duty of a wise people to discourage and restrain it.

The name of American, which belongs to you, in your national capacity must always exalt the just pride of Patriotism, more than any appellation derived from local discriminations.

While Washington famously cautioned that the United States should stay “steer clear of permanent Alliances with any portion of the foreign world,” his views should not be confused with isolationism. Rather, he suggested that the country should be guided by the “common interest [substitute national interest]” and “observe good faith and justice towards all nations.”

Drafting of the Farewell Address: The Farewell Address was truly a collaborative effort by Washington and two of the most brilliant minds of the founding generation, Hamilton and Madison. According to Ellis in Founding Brothers, “Some of the words were Madison’s; most of the words were Hamilton’s; all of the ideas were Washington’s.”

Historian Henry Cabot Lodge agreed that “The thoughts and the general idea of the Farewell Address as all Washington’s. The form, the arrangement, and the method of argument are Hamilton’s.” Copied below is one of Hamilton’s handwritten drafts which can be viewed at the Library of Congress.

When Washington was nearing the end of his first term he shared his outline for the address with Madison in May of 1792. Madison took extensive notes during three meetings with Washington, before preparing the first draft, which used Washington’s own language for many key sections. Washington saved the draft after he was convinced by the unanimous advice of his cabinet to serve a second term.

Four years later, in May of 1796, Washington sent Hamilton the prior draft. Washington offered Hamilton the chance to work from Madison’s earlier draft or entirely rewrite it. Hamilton being Hamilton, he did both, giving Washington the chance to select the reworked draft or select Hamilton’s own new draft. Washington selected the new Hamilton draft, which the two refined together over the summer of 1796.

Out of loyalty to Washington, Hamilton did not advertise his role in drafting the Farewell Address. Decades later, Eliza Hamilton recalled that:

Shortly after the publication of the address, my husband and myself were walking in Broadway, when an old soldier accosted him, with a request of him to purchase General Washington’s Farewell address, which he did and turning to me said ‘That man does not know he has asked me to purchase my own work.'”

When carefully parsed, there is no doubt that the opening paragraphs were largely unchanged from Madison’s first draft. In 1796 the first thing that Hamilton did was prepare a digest, which he called the Abstract of points to form an address. Hamilton used the Abstract as an outline to faithfully capture Washington’s ideas while preparing the new draft. Notwithstanding Hamilton’s substantial edits, Washington wrote out the final version of the address in his own handwriting and Washington was the final editor.

Washington approached Hamilton seeking his assistance with the address in February of 1796 when the two met in Philadelphia. Hamilton had stepped down as Secretary of Treasury but was in town to argue the case of Hylton v. United States at the Supreme Court. Click here for a discussion of the Carriage Act of 1794 that Hamilton successfully defended.

In a letter to Washington dated 5/10/1796 Hamilton followed up and requested the prior draft so he could begin work with the requisite degree of “great care.” Hamilton clearly understood that he was writing for posterity:

When last in Philadelphia you mentioned to me your wish that I should re dress a certain paper which you had prepared. As it is important that a thing of this kind should be done with great care and much at leisure touched & retouched, I submit a wish that as soon as you have given it the body you mean it to have that it may be sent to me.

Less than a week later Washington replied to Hamilton in a letter dated 5/15/1796:

My wish is, that the whole may appear in a plain stile; and be handed to the public in an honest; unaffected; simple garb.

All these ideas, and observations are confined, as you will readily perceive, to my draft of the validictory Address.

For the next two months Hamilton worked on the new draft. Hamilton provided his handiwork in a letter to Washington dated 7/30/1796:

“I have the pleasure to send you herewith a certain draft which I have endeavoured to make as perfect as my time and engagements would permit. It has been my object to render this act importantly and lastingly useful, and avoiding all just cause of present exception, to embrace such reflections and sentiments as will wear well, progress in approbation with time, & redound to future reputation. How far I have succeeded you will judge.”

Washington replied that Hamilton’s new draft was “extremely just,” but could be shortened:

A cursory reading it has had, and the Sentiments therein contained are extremely just, & such as ought to be inculcated. The doubt that occurs at first view, is the length of it for a News Paper publication; and how far the occasion would countenance its appearing in any other form, without dilating more on the present state of matters, is questionable. All the columns of a large Gazette would scarcely, I conceive, contain the present draught. Washington to Hamilton 8/10/1796.

As the team refined the final product, Washington concluded that he appreciated Hamilton’s editing. In particular, Washington approved of the way that Hamilton removed Washington’s “egotism” and made the final draft “more dignified”:

I have given the Paper herewith enclosed several serious & attentive readings; and prefer it greatly to the other draughts, being more copious on material points; more dignified on the whole; and with less egotism. Washington to Hamilton 8/25/1796.

Historian Samuel Flagg Bemis explained that “Despite Hamilton’s principal part in the phrasing of the document, and his previous expression of some of the ideas, we may be sure that in the final text the two men were thinking together in absolute unison.” According to historian Marie Hecht, “It was a true marriage of minds, the peak of amity and understanding between the two men, the final expression of the great collaboration between the first President of the United States and the founder of its financial system.”

Washington’s Views on the Role of Religion: Washington wrote that “Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, religion and morality are indispensable supports.” Copied below are other passages dealing with Washington’s thoughts on religion and morality.

Where is the security for property, for reputation, for life, if the sense of religious obligation desert the oaths which are the instruments of investigation in courts of justice ? And let us with caution indulge the supposition that morality can be maintained without religion. Whatever may be conceded to the influence of refined education on minds of peculiar structure, reason and experience both forbid us to expect that national morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle.

Observe good faith and justice towards all nations; cultivate peace and harmony with all. Religion and morality enjoin this conduct; and can it be, that good policy does not equally enjoin it – It will be worthy of a free, enlightened, and at no distant period, a great nation, to give to mankind the magnanimous and too novel example of a people always guided by an exalted justice and benevolence.

The name of American, which belongs to you in your national capacity, must always exalt the just pride of patriotism more than any appellation derived from local discriminations. With slight shades of difference, you have the same religion, manners, habits, and political principles. You have in a common cause fought and triumphed together; the independence and liberty you possess are the work of joint counsels, and joint efforts of common dangers, sufferings, and successes.

Historic significance of the Farewell Address: Despite their tenuous relationship with Hamilton, in 1825 both Jefferson and Madison recommended that the Farewell Address be studied by students at the University of Virginia as one of the “best guides” for learning “principles of the government” of the United States. During the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln issued a proclamation in 1862 recommending that the American people celebrate Washington’s birthday with public readings of “his immortal Farewell Address.”

Each year the U.S. Senate continues the tradition, with a member reading the Farewell Address on the Senate floor. On average it takes about 45 minutes to read the address. In 1985, Florida Senator Paula Hawkins read the address in a record-setting 39 minutes. West Virginia Senator Jennings Randolph took 68 minutes at a more leisurely pace. The Farewell Address was one of the first recordings that Thomas Edison marketed in 1913.

Contemporary reaction: The Farewell Address was well received around the world. For example, the Earl of Radnor wrote to Washington on January 19, 1797 from Longford Castle near Salisbury, England that:

“Tho’ of Necessity a Stranger to You, I cannot deny myself the Satisfaction among the Many, who will probably even from this Country intrude upon your Retirement, of offering to You my Congratulations on your withdrawing yourself from the Scene of public Affairs with a Character, which appears to me perfectly unrivalled in History”

The New Jersey legislature unanimously declared that Washington’s Address was “replete with sentiments of political wisdom, truth and justice, and merits our grateful acknowledgement.” In a letter from Speaker J. H. Imlay dated November 15, 1796, the Assembly hoped that Washington’s successor:

will be emulous to imitate his virtues and pursue the wise and wholsome system of politics, which has so conspicuously distinguished his administration, and so effectually secured to us the inestimable blessings of Peace, and the present unparallelled prosperity of our country.

Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall observed that the address spoke to “precepts to which the American statesman can not too frequently recur.”

YouTube recordings of Lin-Manuel and Christopher Jackson performing One Last Time:

Original cast recording from Hamilton the Musical

Performance at the White House in 2015

“44 Remix” with Barack Obama, Christopher Jackson and Bebe Winans

Full text of the Farewell Address

Additional reading:

Washington final manuscript at the NY Public Library

Annual reading of the Farewell Address at the Senate (Senate.gov)

Primary Documents pertaining to the Farewell Address (Library of Congress)

Washington’s Farewell Address (Lehrman Institute)

Washington’s papers (GWpapers.Virginia.edu)

Responses to the Farewell Address (GWpapers.Virginia.edu)

Five Lessons We Can Learn from Washington’s Farewell Address (National Constitution Center)

Washington Eulogy by Henry Lee (MountVernon.org)

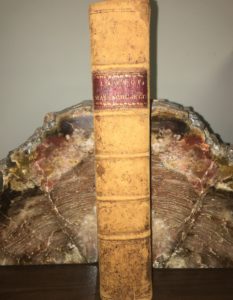

Pictured below is a copy of Washington’s Farewell Address that was printed by patriot publisher Isaiah Thomas in an 1807 edition of The Laws of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Ordinarily, one would not expect to find federal authorities in a state law book, which only serves to reinforce the point that Washington’s Farewell Address was no ordinary speech.

Very enlightening. I had wrongly thought Hamilton basically wrote it all with little editing from Washington.