Declaration of War: the U.S. enters World War I (April 2, 1917)

Statutes at Large, Acts of the 65th Congress, 1st Session

This post discusses the Acts of the 65th Congress which were adopted in connection with the entry of the United States into World War I in 1917.

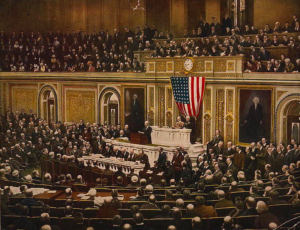

At 8:32 p.m. on April 2, 1917 President Woodrow Wilson entered the chamber of the House of Representatives and began his address asking Congress to declare war against Germany. Approximately half way through the speech, Wilson proclaimed that the world must be made “safe for democracy.” Click here for a link to Wilson’s address.

Wilson described the noble goals of the war. We would not fight for conquest or domination, but for:

the ultimate peace of the world and for the liberation of its peoples, the German peoples included: for the rights of nations great and small and the privilege of men everywhere to choose their way of life and of obedience. The world must be made safe for democracy. Its peace must be planted upon the tested foundations of political liberty. We have no selfish ends to serve. We desire no conquest, no dominion. We seek no indemnities for ourselves, no material compensation for the sacrifices we shall freely make. We are but one of the champions of the rights of mankind. We shall be satisfied when those rights have been made as secure as the faith and the freedom of nations can make them.

After the speech Senator Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts, one of Wilton’s staunchest political adversaries, rushed forward and shook his hand. “Mr. President, you have expressed the loftiest sentiments of the American people.” Wilson replied to an aide, “Think what it was they were applauding…my message today was a message of death for our young men.”

In 1916 Wilton had been reelected with a campaign theme of “We didn’t go to war.” Yet, after months of trying to keep America out of the unprecedented worldwide hostilities, Wilson pressed ahead to save democracy.

In the month of February, 1917, German U-boats sank five American ships. Germany had decided on a policy of unrestricted submarine warfare, believing that even if the U.S. declared war, it would be too slow to mobilize to make a difference in the short term. Germany gambled that its U-boats could end the war by cutting off supplies to the allies, before an American army could be sent to Europe.

In the month of February, 1917, German U-boats sank five American ships. Germany had decided on a policy of unrestricted submarine warfare, believing that even if the U.S. declared war, it would be too slow to mobilize to make a difference in the short term. Germany gambled that its U-boats could end the war by cutting off supplies to the allies, before an American army could be sent to Europe.

British intelligence was also warning of a telegram from the German foreign secretary Arthur Zimmerman to the German ambassador in Mexico that Germany would restore the “lost territories” of Texas, Arizona and New Mexico, if Mexico would join the war. In addition to the German attacks on American shipping, other factors that convinced Congress to join the allies included U.S. economic investments in Europe and cultural links to England and the allied democracies. After four days of debate, the House voted 373 to 50 for war. The Senate vote even closer, 82 to 6. The U.S. officially entered the “Great War” on April 6, 1917.

Pictured and described below are several major acts of Congress that were adopted as the U.S. entered World War I:

Compared to the European nations which had been fighting since 1915, the American casualty rate after 19 months was a relatively modest 8%. By contrast, European armies sustained casualties of 70%. Whereas much of Europe was decimated by the war, the American mainland was untouched. Nevertheless, the “Great War” was a pivotal turning point in American history. The war not only impacted the lives of the hundreds of thousands of Americans “doughboys” who fought “over there,” the war effort also helped transform American society, the economy, government and foreign policy in ways that could not have been anticipated by Wilson. This post describes several of the major acts of Congress that were adopted in 1917 as the U.S. mobilized for its first world war.

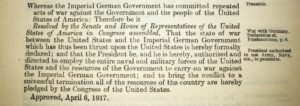

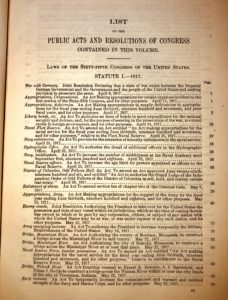

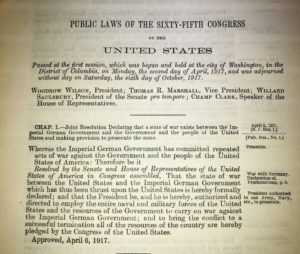

The Joint Resolution Declaring War with Germany (40. Stat. 1): The joint resolution declared that a state of war existed between the Imperial German Government and the Government of the people of the United States. Whereas a state of war had been “thrust upon the United States” Congress “formally” declared war and authorized President Wilson to “employ the entire naval and military forces of the United States and the resources of the Government to carry on war against the Imperial German Government; and to bring the conflict to a successful termination.” In the declaration Congress pledged “all of the resources of the country.” The Declaration of War against Austria-Hungary followed on December 11, 1917.

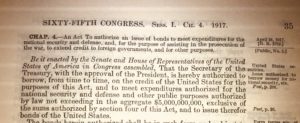

Liberty Loan Act (40 Stat. 35-37): Adopted in the same month of the Declaration of War, the Act authorized the issuance of $5 billion in long term Liberty bonds to be sold at public auction to raise funds for war expenditures and loans to allies. Ultimately five different bond issues were subscribed between May of 1917 and April of 1919, totaling $21.5 billion.

Selective Service Act (40 Stat. 76-83): Building on Lincoln’s Conscription Act of 1863, the Selective Service Act required “all male citizens, or male persons not alien enemies who have declared their intention to become citizens” (between the ages of 21 and 30) to register for military service. The Act was adopted in May of 1917 and provided for classification of registrants according to their fitness and established a lottery system to determine the order of induction. Unlike the conscription system employed during the Civil War, the Selective Service Act prohibited the hiring of substitutes.

Espionage Act (40 Stat. 217-231): Provided for terms of imprisonment of up to 20 years and fines of up to $10,000 for persons found guilty of spying, sabotage, refusing military service, or obstructing recruitment. Recalling the Alien and Sedition Acts of the 5th Congress, the Espionage Act empowered the Postmaster General to withhold mailing privileges from all newspapers and other publications determined to be seditious. The Act was amended by the Sedition Act which established criminal penalties for: willfully making “false report or false statements with intent to interfere with the operation or success of the military or naval forces of the United States,” promoting the success of enemies of the U.S., employing “disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language” about the government, Constitution, flag, or military of the U.S.

Trading with the Enemy Act (40 Stat. 411-426): Prohibited commercial dealings with the nations at war with the United States and authorized the President to place embargoes on imports. The Office of Alien Property Custodian was established to take possession of property. The Act also established the War Trade Board to license imports and exports and enforce trade restrictions.

Other acts adopted during World War I included the 18th and 19th Amendments, the Daylight Standard Time Act, and the Railroad Control Act. Click here for a link to all of the Acts of the 65th Congress.

Also important to the war effort were wartime agencies that helped organize and direct public and private resources, including the War Industries Board (led by Bernard Baruch), the National War Labor Board (chaired by William Howard Taft), the Food Administration (headed by Herbert Hoover), and the Committee on Public Information. The membership of the boards were appointed by President Wilson, who was authorized to coordinate executive agencies during the duration of the war by the Overman Act (40 Stat. 556-557).

Each of these acts will be explored in greater detail in future posts.