The the Militia Acts of 1792 (the “Calling Forth” Act and the Act “Establishing a Uniform Militia”)

The first Militia Act, May 2, 1792 (Calling Forth Act, ch. 28, 1 Stat. 264)

The Second Militia Act, May 8, 1792 (Establishing Uniform Militia, ch. 33, 1 Stat. 271)

The philosophy of “peace through strength” is associated with President Ronald Reagan. Yet, this concept made famous by President Reagan can be traced back to President George Washington and his first Annual Address to Congress on January 8, 1790. For Washington, “[t]o be prepared for war is one of the most effectual means of preserving peace.”

As described below, the Militia Acts of 1792 were reluctantly adopted by the Second Congress at President Washington’s urging. The Militia Acts were finally adopted on the last day of the first Session of the Second Congress. President Washington would later invoke the Militia Acts when responding to the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794. A forthcoming post will discuss the debate at the Constitutional Convention over war powers and the dangers of a standing army.

Background: In his first Annual Address on January 8, 1790, President Washington laid out his goals for a well regulated militia:

Among the many interesting objects which will engage your attention that of providing for the common defense will merit particular regard. To be prepared for war is one of the most effectual means of preserving peace.

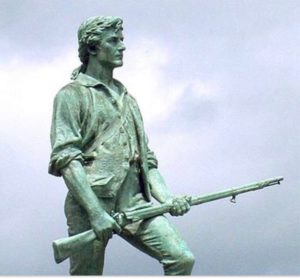

A free people ought not only to be armed, but disciplined; to which end a uniform and well-digested plan is requisite; and their safety and interest require that they should promote such manufactories as tend to render them independent of others for essential, particularly military, supplies.

The proper establishment of the troops which may be deemed indispensable will be entitled to mature consideration. In the arrangements which may be made respecting it it will be of importance to conciliate the comfortable support of the officers and soldiers with a due regard to economy.

The use of military force was a controversial subject that the first Congress avoided. Of course, the enormously successful first Congress was preoccupied with establishing the new federal government and writing the laws that created the Department of Foreign Affairs (Laws of the 1st Congress, Chapter IV), the Department of War (Chapter VII) and the Department of the Treasury (Chapter XII), among other foundational laws passed in 1789. Click here for a discussion of how the First Congress (1789 – 1791) brought the Constitution to life under the leadership of James Madison.

Yet, on the last day of the session, September 29, 1789, the First Congress adopted an Act to enable the President to call up the militia for the limited purpose of protecting the inhabitants of the frontiers from “the hoftile incurfions of the Indians” (Chapter XXV). The cautious First Congress specified that the Act had a limited duration and would continue in force until the end of the next session of Congress “and no longer.”

Eventually, one of the worst military defeats in American history forced the Second Congress to directly and more comprehensively address the President’s emergency power as Commander and Chief to deploy state militias. In November of 1791 in the Battle of the Wabash River (also known as St. Clair’s Defeat and the Battle of a Thousand Slain) the nascent U.S. military suffered a historic defeat by Chief Little Turtle during the Northwest Indian Wars. After the battle, approximately half of the entire U.S. Army was killed or wounded (out of a force of 1,400, 918 were killed and 276 wounded). These losses would not be replicated until Custer’s last stand at Little Big Horn in 1876.

Following the battle, President Washington forced General St. Clair to resign and the House initiated its first Congressional investigation of the executive branch. On May 8, the last day of the session, the Annals of Congress reflect that the Committee appointed to inquire into “the causes of the failure of the late expedition of Major General St. Clair” made its report, which was read aloud in the House chamber.

In passing the Militia Acts Congress was also well aware of Shay’s Rebellion in western Massachusetts (1786-1787), which was one of the motivations for the calling of the Constitutional Convention in the first place.

The Militia Acts: The “Militia Act of 1792” consists of two separate acts, adopted six days apart by the Second Congress. The first Militia Act was adopted on May 2, 1792 and is also known as the “Calling Forth Act” because it delegated power to the President to call up state militias. The second Militia Act, also known as the “Uniform Militia Act,” was adopted on May 8, 1792 and addressed the regulation of state militia and the conscription of troops.

Calling Forth Act: The Calling Forth Act empowered the President to call forth the militia under three sets of circumstances: invasions, insurrections, or when the laws of the United States were opposed by “combinations too powerful to be suppressed by the ordinary course of judicial proceedings.”

These criteria largely track Article I, Section 8, clause 15 of the Constitution (the first Militia Clause), with one critical difference. The Constitution specifies that Congress has the power to call forth the militia. While Article II designates the President as the Commander in Chief, this authority was limited to when the militia “was called into the actual service of the United States.” Thus, the first Militia Act represented an expansion of presidential war authority, through express delegation by Congress. Of course, Congress understood that without this authority, the President’s hands were tied when Congress was otherwise not in session.

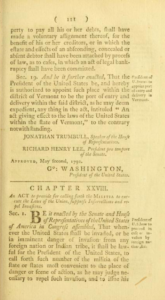

While not explicitly authorized by the Constitution, Section 1 of the Act provided the President the unilateral authority to respond to invasions and insurrections as follows:

That whenever the United States shall be invaded, or be in imminent danger of invasion from any foreign nation or Indian tribe, it shall be lawful for the President of the United States, to call forth such number of the militia of the state or states most convenient to the place of danger or scene of action as he may judge necessary to repel such invasion, and to issue his orders for that purpose, to such officer or officers of the militia as he shall think proper; and in case of an insurrection in any state, against the government thereof, it shall be lawful for the President of the United States, on application of the legislature of such state, or of the executive (when the legislature cannot be convened) to call forth such number of the militia of any other state or states, as may be applied for, or as he may judge sufficient to suppress such insurrection.

Section 2 of the Act attempted to partially circumscribe the President’s authority when the laws of the United States were being obstructed. Unlike cases of invasion or insurrection addressed by Section 1, the President did not have the same unilateral authority under Section 2 unless he was notified by an associate justice or district judge that those opposed to the execution of the law could not be suppressed by the ordinary course of judicial proceedings. Section 2 further set forth the following limitations and safeguards:

And if the militia of a state, where such combinations may happen, shall refuse, or be insufficient to suppress the same, it shall be lawful for the President, if the legislature of the United States be not in session, to call forth and employ such numbers of the militia of any other state or states most convenient thereto, as may be necessary, and the use of militia, so to be called forth, may be continued, if necessary, until the expiration of thirty days after the commencement of the ensuing session.

The specific authorization for the President to call up the militia during a recess of Congress was added upon a motion by James Madison. Click here for a link to the Congressional debates in the Annals of Congress.

Section 3 imposed the reasonable requirement that before military force was used against insurgents the President would “by proclamation, command such insurgents to disperse, and retire peaceably to their respective abodes, within a limited time.”

Section 4 specified that members of the militia were entitled to receive the same pay and allowances as the regular troops of the United States. Recognizing the members of the militia were citizen soldiers, Section 4 further provided that members of the militia could not be compelled to serve more than three months in any one year.

The final paragraph of the Act, Section 10, provided that the Act shall sunset after two years “and no longer.” The limited duration of the Act was likely based on a recognition that Congress was pushing the limits of its authority to delegate war powers. Congress may also have been trying to pay deference to the constitutional requirement in Article I, Section 8 that Congressional appropriations for the army shall not last longer than two years.

The Uniform Militia Act: The Second Militia Act of 1792 (the Uniform Militia Act) was an effort to better organize the militia as recommended by Secretary of War Henry Knox. The ambitious act presumed that the states and citizen soldiers (at their own expense) were ready and willing to comply with the detailed requirements envisioned by Congress. The Act provided for the enrollment of “every free able-bodied white male citizen” between the ages of 18 and 45 into a militia company within 12 months.

Section 1 of the Act further required each citizen to arm themselves with the following:

That every citizen so enrolled and notified, shall, within six months thereafter, provide himself with a good musket or firelock, a sufficient bayonet and belt, two spare flints, and a knapsack, a pouch with a box therein to contain not less than twenty-four cartridges, suited to the bore of his musket or firelock, each cartridge to contain a proper quantity of powder and ball: or with a good rifle, knapsack, shot-pouch and powder-horn, twenty balls suited to the bore of his rifle, and a quarter of a pound of powder; and shall appear, so armed, accoutred and provided, when called out to exercise, or into service, except, that when called out on company days to exercise only, he may appear without a knapsack.

Members of Congress and a handful of critical occupations were exempted from conscription, including mariners, custom-house officers, ferryboatmen and stagecoach drivers employed on post roads, and those otherwise exempted under state law.

Section 3 of the Act provided for the militia in each state to be arranged into divisions, brigades, regiments, battalions and companies. Sections 4-7 provided for detailed organizational requirements including training and rules of discipline.

Section 9 created a right to disability benefits for those injured in the line of duty as follows:

Provision in case of wounds, &c. That if any person, whether officer or soldier, belonging to the militia of any state, and called out into the service of the United States, be wounded or disabled while in actual service, he shall be taken care of and provided for at the public expense.

Constitutional Authority: Article I, Section 8 of the U.S. Constitution contains two “Militia Clauses” granting Congress the power to call forth and organize state militias. The first Militia Clause empowers Congress to call forth the state militias to “execute the laws of the union, suppress insurrections and repel invasions.” The second Militia Clause authorizes Congress to provide for the “organizing, arming, and disciplining” of the militia. Both clauses are quoted in their entirety below.

Under Article I, Section 8 Congress has the power:

To provide for calling forth the Militia to execute the Laws of the Union, suppress Insurrections and repel Invasions;

To provide for organizing, arming, and disciplining, the Militia, and for governing such Part of them as may be employed in the Service of the United States, reserving to the States respectively, the Appointment of the Officers, and the Authority of training the Militia according to the discipline prescribed by Congress.

Article II of the Constitution grants the President power as the Commander in Chief over the army, navy and state militias when called into service of the United States.

Article II, Section 2, provides as follows:

The President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the Militia of the several States, when called into the actual Service of the United States.

A discussion of the militia clauses would be incomplete without a citation to the Second Amendment which provides as follows:

A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.

As explained by historian Joseph Ellis in the book The Quartet, James Madison’s intent when drafting the Second Amendment was to allay the concerns of several states which sought an amendment prohibiting a permanent standing army. For Madison, a well organized militia could help provide for the common defense and would obviate the need for a large standing army.

Additional reading:

Stephen I. Vladeck, Emergency Power and the Militia Acts, Yale Law Review (2004)

Citizen-Soldiers, Creating a well-regulated militia (lawsonline.com)

Francis Drake, Life and Correspondence of Henry Knox (1873)

Catherine Drinker Bowen, Miracle at Philadelphia: The story of the Constitutional Convention (1966)

Christopher Collier & James Collier, Decision in Philadelphia: The Constitutional Convention of 1787 (2007)

Richard H. Kohn, The Eagle and Sword: The beginnings of the Military Establishment in America (1975)

The first Militia Act (the Calling Forth Act) is copied below:

The second Militia Act (the Uniform Militia Act) is copied below: