The “first” Thanksgiving and Washington’s Thanksgiving Proclamations

The “first” Thanksgiving in 1621: While Native Americans had likely been celebrating harvests for thousands of years, the “first” Thanksgiving in 1621 was a harvest celebration by the Pilgrims of Plymouth colony. The fifty-three Pilgrims who survived their first winter had much to be thankful for.

Out of the 102 Pilgrims who departed from Plymouth, England, forty-eight did not survive to celebrate. Five Pilgrims passed away during the sixty-five day trip on the Mayflower. Starvation and disease claimed approximately forty-five more lives during the brutal winter of 1620-1621.

The Thanksgiving story appropriately credits the local Wampanoag tribe who provided assistance to the Pilgrims and were guests during the first Thanksgiving feast. Central characters in the story include Wampanoag leader Massasoit, Squanto (the former slave and translator), and “Pilgrim Fathers” William Bradford and Myles Standish.

The first-hand story of the first Thanksgiving is told by Plymouth Governor William Bradford in his two volume History of Plymouth Plantation 1620-1647 (Volume I) and (Volume II). The only other primary source is Edward Winslow’s Journal of the Plantation at Plymouth.

Winslow’s journal records the following:

[O]ur harvest being gotten in, our governour sent foure men on fowling, that so we might after a speciall manner rejoyce together, after we had gathered the fruits of our labours ; they foure in one day killed as much fowle, as with a little helpe beside, served the Company almost a weeke, at which time amongst other Recreations, we exercised our Armes, many of the Indians coming amongst us, and amongst the rest their greatest king Massasoyt, with some ninetie men, whom for three dayes we entertained and feasted, and they went out and killed five Deere, which they brought to the Plantation and bestowed on our Governour, and upon the Captaine and others. And although it be not always so plentifull, as it was at this time with us, yet by the goodness of God, we are so farre from want, that we often wish you partakers of our plentie.

While Winslow’s narrative is widely considered as the basis for today’s Thanksgiving tradition, similar first “Thanksgivings” occurred in St. Augustine, Florida in 1565 and Jamestown, Virginia in 1619.

Pictured below is “the First Thanksgiving at Plymouth” by Jennie Brownscombe (1914).

Colonial Thanksgivings: During the colonial period, Thanksgiving was understood as a religious holiday. Days of Thanksgiving, prayer and fasting were periodically declared for different reasons and at different times. For example, during a drought in 1623 Plymouth Governor Bradford declared a day of fasting and prayer as “a solemn day of humiliation, to seek the Lord by humble and fervent prayer, in this great distress.” In the evening when it began to rain, a day of Thanksgiving was declared.

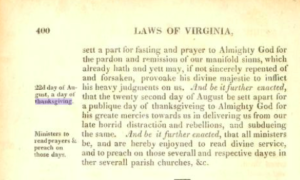

Copied below is an Act of the Virginia House of Burgesses in 1644 establishing the last Wednesday in every month as a day of “ffast and humiliation” dedicated to prayers and preaching.

Following Bacon’s Rebellion of 1676 and the burning of Jameston, an “Act for setting forth a day of humiliation and a day of Thanksgiving” was adopted by the Virginia House of Burgess. The “publique day” of thanksgiving, fasting and prayer was declared for August 2, 1677.

Washington’s Thanksgiving Proclamations: The first Thanksgiving proclamation during the Revolutionary War was issued by John Hancock, the President of the Continental Congress. Hancock called for a day of fasting on March 16, 1776 after the British evacuated Boston. Following General Burgoyne’s surrender to the Americans at the battle of Saratoga in October of 1777, the Continental Congress recommended that a day be set aside to celebrate the American victory. General Washington agreed and proclaimed December 18, 1777 as a national Thanksgiving day.

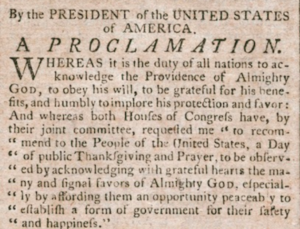

In 1789, in celebration of the ratification of the Constitution and the establishment of the new federal government, President Washington issued a proclamation declaring November 26 as a national day of thanksgiving. Click here for a link to President Washington’s first Thanksgiving proclamation. The proclamation was distributed to state governors, with the request that governors announce and observe the day within their respective states. Washington marked the day by attending services at St. Paul’s Chapel in New York City. Recognizing that he was a national symbol, Washington donated beer and food to imprisoned debtors in New York, the nation’s first capitol.

Washington called on Americans to thank G-d for protection and mercy during the Revolutionary War and “for the great degree of tranquillity, union, and plenty, which we have since enjoyed.” Washington also noted that “we have been enabled to establish constitutions of government for our safety and happiness, and particularly the national One now lately instituted—for the civil and religious liberty with which we are blessed.”

Washington’s 1795 Thanksgiving proclamation: Washington’s second Thanksgiving proclamation was declared on January 1, 1795, following the Whiskey Rebellion. Washington observed that America was blessed with a “great degree of internal tranquillity,” notwithstanding the “insurrection” that he and Alexander Hamilton had personally suppressed with approximately 13,000 troops. Click here for a discussion of the Whiskey Rebellion. Washington also noted that Europe was being torn apart by war between Britain and France, which he would avoid with his Neutrality Proclamation of April 22, 1793 and Jay’s Treaty with England. Click here for a discussion of Jay’s Treaty:

When we review the calamities which afflict so many other Nations, the present condition of the United States affords much matter of consolation and satisfaction. Our exemption hitherto from foreign war, an increasing prospect of the continuance of that exemption, the great degree of internal tranquillity we have enjoyed, the recent confirmation of that tranquillity by the suppression of an insurrection which so wantonly threatened it, the happy course of our public affairs in general, the unexampled prosperity of all classes of our Citizens —are circumstances which peculiarly mark our situation with indications of the Divine Beneficence towards us. In such a state of things it is, in an especial manner, our duty as a people, with devout reverence and affectionate gratitude, to acknowledge our many and great obligations to Almighty God and to implore him to continue and confirm the blessings we experience.

Washington’s 1795 Thanksgiving Proclamation declared February 19th as a day of public thanksgiving and prayer. Click here for a link to Washington’s 1795 Thanksgiving proclamation. Click here for the original draft, which was written by Alexander Hamilton. Washington used Hamilton’s draft in its entirety, with only minor edits.

While Washington declared two Thanksgiving holidays during his eight years a President, the event did not become a regular annual holiday until 1863. New York became the first state to officially adopt an annual Thanksgiving holiday in 1817. Click here for a discussion of Lincoln’s Thanksgiving Proclamation of 1863.

Proclamations v. Executive Orders: Presidential proclamations are easily confused with executive orders. Generally speaking, executive orders are directed to those within the government, particularly the executive branch, while Presidential proclamations are addressed to a wider audience.

During his two terms as President, Washington issued 27 proclamations. His most controversial proclamation was his Neutrality Proclamation issued on April 22, 1793.

Of all of the “founding father” presidents, James Madison issued the most proclamations with a total of 39. Madison also issued the largest number of proclamations in a single term, 27, the same number issued by Washington during two terms.

Not surprisingly, President Jefferson issued the fewest proclamations. In his first term, the anti-ceremonial Jefferson issued only 4 proclamations.

George Washington and Thanksgiving (Mount Vernon)

Christopher Young, Proclamations and the Founding Father Presidents, 1789–1825

The History of the First Thanksgiving (Massachusetts Historical Society)

Squanto: The Former Slave (Massachusetts Historical Society)

The History of the Mayflower Ship (Massachusetts Historical Society)

The now famous Plymouth gathering didn’t jump-start Thanksgiving (Washington Post)

The Thanksgiving Story You’ve Probably Never Heard (New York Times)

Pilgrim Hall Museum

Virginia Act XVIII of 1676:

Where in the Constitution is the President given authority to issue a proclamation regarding Thanksgiving?

Good question. Article II of the Constitution is fairly concise. In my mind, there are at least two provisions that indirectly permit the President to issue proclamations: 1) Article II, Section 1, vests the Executive Power in the President and 2) Article II, Section 3 provides that the President “shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.”

You would be correct to note that Jefferson was reluctant to issue proclamations. You would also be correct to blame Congress for failing to object to the gradual expansion of executive authority over time. In the case of presidential proclamations, I would respond that the result has been largely innocuous.