THE EMOLUMENTS CLAUSE – What did the Founders Intend?

Part 1 – Examples of the treatment of diplomatic gifts by the founders

The Emoluments clauses of the United States Constitution had never been tested in court until recent challenges were brought by the State of Maryland, the District of Columbia, and Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington (CREW). The legal briefs in the pending litigation cite to the legislative history surrounding the drafting of the Constitution in Philadelphia in 1787 and the subsequent state ratification debates, along with the Eighteenth Century understanding of the term “emolument.”

The parties’ briefs also cite to several examples of the treatment of diplomatic gifts during the formative years of American history. Statutesandstories.com has located a handful of additional historical examples that are not believed to have been cited by the parties. It is felt that these further examples may be useful for the courts as the litigation proceeds.

Statutesandstories also hopes to provide meaningful historical background for two examples that were cited in pending litigation. Yet, a cursory view of these gifts, without placing them in their proper context during the height of the French Revolution, risks doing harm to Washington’s motivations and reputation.

This memo is divided into two parts. Part I discusses additional un-cited examples that help shed light on the treatment of emoluments by the founding generation. Part II attempts to place the two symbolic gifts received by President Washington during critical moments of the French Revolution into their proper historical context. Both parts of this memo support the broad reading of the Emoluments Clauses.

Part I: Additional examples of compliance with the Foreign Emoluments clause:

Part I of this post cites and summarizes several examples of compliance with the Foreign Emoluments clause that are not believed to have been cited in the cases pending in the Southern District of New York or the District of Maryland. The examples illustrate the framers’ understanding of the “Foreign Emoluments” clause in Article I of the U.S. Constitution (variously known as the Article I Emoluments Clause, Gifts Clause, Foreign Gifts Clause, and Foreign Titles Clause) and also bear on the Article II Emoluments Clause.

The prompt return of ancient Roman gold coins by the three American diplomats, including Chief Justice Ellsworth, who negotiated the Treaty of Mortefontaine in 1800, after consulting with the Secretary to the Diplomatic Mission, Jurist Zephaniah Swift:

On or about September 30, 1800, American diplomats Oliver Ellsworth, William Davie, and William Vans Murray promptly returned gold Roman coins presented as gifts by Napoleon Bonaparte following the successful negotiation of the Treaty of Mortefontaine. The American diplomats agreed that returning the coins (also described as medals) was required by the Foreign Emoluments clause, after consulting with the Secretary of the delegation and legal advisor, Zephaniah Swift.

The biographer William Garrott Brown in the book The Life of Oliver Ellsworth[1] describes the scene[2] when Napoleon Bonaparte (at the time the First Consul of France) offered gold coins to the American diplomats:

The First Consul, it seems, had directed the minister of foreign affairs to present to each of the American ministers a costly gift. Moreover, the prefect of L’Oise having brought to the fete, as a present to the First Consul himself, a basketful of gold medals of different periods of the Roman republic, which had been found in his department, Napoleon remarked that the best possible disposition of these relics of a great republic was to them to the citizens of the American republic. He accordingly gave a handful to each of the three.

A few minutes later, the company observed the Americans retire into the recess of a window, and there engage in an animated controversy with their secretary, who, as it afterwards appeared, had reminded them that Americans employed in diplomatic officers were forbidden to accept gifts from foreign governments. Roederer [one of the French diplomats who recorded the story in his journals][3] was of the opinion that the secretary, having been overlooked in the distribution of the medals, mixed some personal pique with his constitutional scruples. The envoys, however, accepted his view, explained their position to the First Consul through the French ministers, and gave back the medals.

Background of the American delegation who negotiated the Treaty of Mortefontaine: The American delegation, who were appointed by President Adams to negotiate an end to hostilities with France, were well positioned to understand the constitutional requirements of the Foreign Emoluments clause. In particular, the fact that this brain trust of framers and scholars deliberated over the application of the Foreign Emoluments clause may be particularly useful:

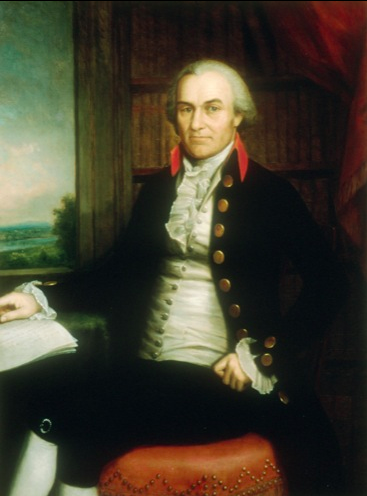

Oliver Ellsworth (framer, Senator and Chief Justice): At the time of his appointment by President Adams to the diplomatic mission to France, Oliver Ellsworth was serving as the third Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court. Ellsworth was a framer of the Constitution who represented the State of Connecticut at the Philadelphia Convention. He served on the five member Committee on Detail which prepared the first draft of the Constitution. He also played a key role with respect to the Connecticut Plan and the Great Compromise.

After advocating for Connecticut to ratify the Constitution, Ellsworth served as one of the state’s first Senators from 1789 to 1796. During the first Congress he was the principal author of the Judiciary Act of 1789, the Process Act of 1789, and the Crime Act of 1790 (otherwise known as the Federal Criminal Code of 1790).[4] Ellsworth also drafted the bill to regulate the consular service[5] and was a key Senate ally of Alexander Hamilton.

William Richardson Davie (framer and Governor): A framer who served as a delegate to the Philadelphia Convention from North Carolina, William Davie supported the Great Compromise. Davie also played an active role at North Carolina’s ratification convention. After a prominent legal career, he was elected Governor of North Carolina in 1798. As a member of the North Carolina Legislature, he sponsored the bill to found the University of North Carolina and was later conferred the title “Father of the University” in 1810.[6]

William Vans Murray (respected diplomat and member of Congress): Vans Murray served three terms in Congress representing Maryland from 1791 to 1797. He was appointed U.S. ambassador to the Netherlands by President Adams in 1797. Murray is recognized for his diplomatic skills, including successfully concluding negotiations over the Dutch-American Treaty of Amity and Commerce.[7] While holding this post, President Adams appointed Murray to the diplomatic mission to France in 1799. Years earlier, Vans Murray had studied law in London, at which time he became a close friend of John Quincy Adams.

During his time in London from 1784 to 1787, Van Murray became a protege of John Adams, who was serving as minister plenipotentiary to Britain. While Vans Murray was not present at the Constitutional Convention, he was the author of six essays published under the pseudonym “Citizen of the United States,” which were addressed to his political mentor, John Adams. Murray’s essays were published in Philadelphia during the Constitutional Convention.

Zephaniah Swift (respect jurist, author and Chief Justice of the Connecticut Supreme Court): The author of the first American legal treatise[8], Zephaniah Swift served in U.S. House of Representatives during the Third and Fourth Congress. Known as “America’s Blackstone,” in 1796 he compiled and edited the first official version of the Laws of the United States. Beginning in 1801 Swift became a Justice on the Connecticut Supreme Court, serving as Chief Justice from 1806 – 1819. Swift also operated a respected law school out of his office for many years.

Additional Background about the Treaty of Mortefontaine: Oliver Ellsworth, William Davie, and William Vans Murray were appointed by President Adams in the year 1800 to attempt to negotiate a peaceful resolution of the undeclared Quasi-War between the United States and France. Respected legal scholar Zephaniah Swift was selected by President Adams to serve as secretary of the mission.

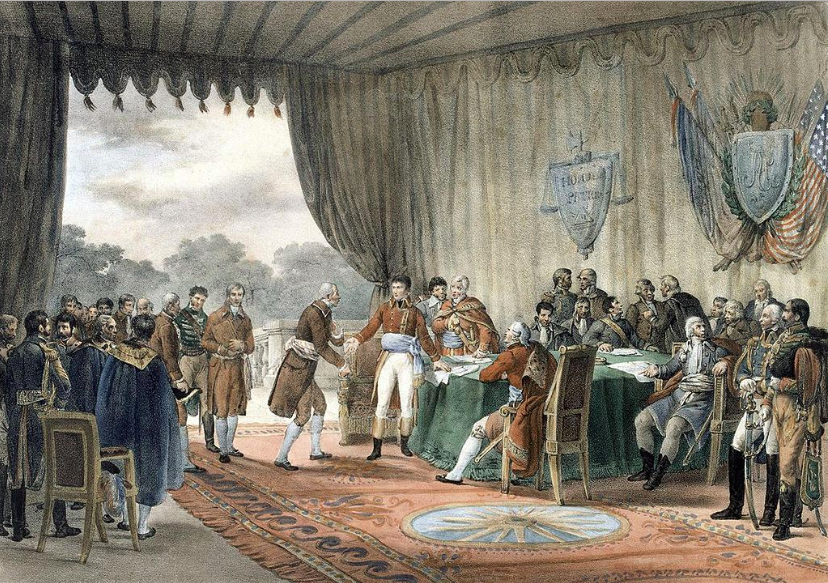

Upon arrival in Lisbon, the American delegation learned that the French Directory (the post-Revolutionary French government) had been dissolved and that Napoleon Bonaparte had seized power as the First Counsel. The French delegation for the negotiations was headed by Joseph Bonaparte (Napoleon’s brother), Pierre-Louise Roederer, and Claret de Fleurieu. After the negotiations were successfully concluded, an elaborate celebration was held at Mortefontaine, Joseph Bonaparte’s country estate north of Paris. The pageantry of the celebration is captured in Victor-Jean Adam’s oil painting pictured below titled, “The signing of the Convention at Mortefontaine, September 30, 1800”[9]:

At the time, active naval battles in the Caribbean were being fought between American and French forces, following the XYZ Affair in the late 1790’s. The successful negotiations with Napoleon and the Marquis de Talleyrand resulted in the Convention of 1800, also known as the Treaty of Mortefontaine. Yet, the Treaty of Mortefontaine was sufficiently controversial in the United States that the first attempt at ratification failed in December of 1800. The treaty was subsequently ratified with amendments in February of 1801.

Arguably, the ability to secure this treaty with Napoleon in 1800 and its resulting goodwill opened the door to the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. President Adams believed the Treaty of Mortefontaine to be one of the most important accomplishments of his Presidency. According to Adams, “I desire no other inscription over my gravestone than ‘Here lies John Adams, who took upon himself the responsibility for peace with France in the year 1800.’” As recognized by President Adams, American history might have been very different if America had been drawn into war with Napoleon.

George Washington’s policy of not staying at private residences while traveling on official business as President:

In a letter[10] dated March 29, 1791 from President Washington to Charles Pickney, Washington explained that he had prescribed for himself a “rule of declining all invitations to quarters on my journies…”:

While I express the grateful sense which I entertain of your Excellency’s polite offer to accommodate me at your house during my stay in Charleston, your goodness will permit me to deny myself that pleasure.

Having, with a view to avoid giving inconvenience to private families, early prescribed to myself the rule of declining all invitations to quarters on my journies, I have been repeatedly under a similar necessity with the present of refusing those offers of hospitality, which would otherwise have been both pleasing and acceptable.

Similarly, in a letter[11] dated January 16, 1791 from George Washington to Edward Rutledge, Washington described his policy of declining accommodations offered at private residences:

It was among my first determinations when I entered upon the duties on my present Office, to visit every part of the United States in the course of my Administration of the Government, provided my health, and other circumstances would admit of it: and this determination was accompanied by another—viz.—not by making my headquarters in private families to become troublesome to them in any of these tours. The first I have accomplished in part only, without departing in a single instance from the second, although pressed to it by the most civil & cordial invitations. After having made this communication to you, you will readily perceive, my dear Sir, that it is not in my power (however it might comport with my inclinations) to change my plan without incurring the charge of inconsistency if not something more exceptionable; especially too, as it is not more than ten days since I declined a similar invitation to yours from my namesake & kinsman Colo. Willm Washington of your ⟨state to⟩ lodge at his house when I should visit Charleston. With affectionate esteem & regard I am—My dear Sir Yr Most Obedt Servt

In denying these “offers of hospitality” from fellow founding fathers and colleagues, Washington politely explains that the accommodations would have been “pleasing.” Nevertheless, Washington’s “rule” likely reflects a motivation not only to avoid imposing on “private families,’ but also to preserve Washington’s independence and rectitude. Washington explained that if he were to depart from his rule, he feared “incurring the charge of inconsistency if not something more exceptionable.”

Only Washington will know why he adopted this policy, but it reflects an intent to maintain an arms length financial relationship with even close associates, which was “among my first determinations when I entered upon the duties on my present Office.” In an earlier description of Washington’s policy, Washington indicated that declining invitations to private residences would leave him “unembarrassed by engagements” and would “avoid giving umbrage to any by declining all such invitations of residence.”[12]

Thomas Jefferson’s quiet sale of diamonds from a “miniature picture of the king set in brilliants” to fund the cost of reciprocal gifts to French diplomats:

In a letter[13] by Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson dated January 24, 1791 to his personal secretary, William Short, Jefferson directed in coded cipher that a diamond encrusted miniature engraving of Louis XVI be disassembled and quietly sold, in order to fund the cost of reciprocal gifts that Jefferson presented to French diplomats.

Based on French diplomatic conventions, Jefferson elected not to return the gift, which arrived at his Paris home on July 19, 1791 after Jefferson had already departed for the United States. Under Short’s supervision, the diamonds were removed and sold with the proceeds being used to offset Jefferson’s reciprocal gifts to French officials and Jefferson’s moving expenses. As explained by Jefferson, “[s]ince Tolozan and Sequeville are decided not to accept their presents unless I accept mine, I must yield as theirs is their livelihood.”

The following text by Jefferson was written in cipher to Short, Jefferson’s secretary:

Since Tolozan and Sequeville are decided not to accept their presents unless I accept mine, I must yield as theirs is their livelihood. Be so good then as to finish that matter by3 the usual exchange of presents in my behalf. Our government having now adopted the usage of making presents in the like case, so as to establish a reciprocity, one of the motives for my refusal is removed, which may be mentioned to them. On recieving therefore the present of congé of usage be so good as to give them4 the twelve and eight hundred livres, mentioned in my letter of April 6 and more if on enquiry from Baron Grimm or any other in whose information you confide you find that more has been usually given by those of my grade, but do not give less than there mentioned. I know indeed that Doctr. Franklin gave considerably more, but that was because he was extravagantly well treated on the occasion himself. To face the expence of the presents to Tolozan and Sequeville you must draw on our bankers in the first instance and as I presume the King’s present will be his picture or something set in diamonds, I must get you my dear Sir to have these taken out of the cadre and disposed of advantageously at Paris, London or Amsterdam and deposit the proceeds with the Van Staphorsts & Hubbard on my account where it will be ready to cover what shall have been given to Tolozan and Sequeville and any further deficiency which may be produced by the expences of my return, or a disallowance of any article of my French accounts. Send to me the cadre, be it picture, snuff box or what it will, by any conveyance, but sealed and unknown to the person who brings it and above all things contrive that the conversion of the present into money be absolutely secret so as never to be suspected at Court, much less find its way into an English newspaper.

It noteworthy that Jefferson instructed Short in coded cipher to make sure that the sale was “absolutely secret so as never to be suspected” by the French Court or the English press. In other words, Jefferson understood the symbolism and potential diplomatic consequences if he were to have refused the gift from King Louis XVI.[14] After paying the reciprocal gifts to the French ambassadors Tolozan and Sequeville, Jefferson may have made a profit on the transaction. Nevertheless, it is doubtful that Jefferson would have known this at the time.

Based on the images located at the Monticello.org and Mountvernon.org websites, it appears that the same duplicate engraving of Louis XVI by Charles-Clement Bervic (based on a portrait by Antoine-Francois Callet) was presented to President Washington by the new French Ambassador, Jean Baptiste Ternant, as described in Professor Tillman’s brief. Thus, the miniature engravings presented to Washington and delivered to Jefferson’s home in Paris should not be confused with the original full size, color portrait of Louis XVI. The engravings are merely reproductions of a famous portrait by Antoine-Francois Callet, which is in the permanent collection at the Louvre.

Images of Brevic’s engravings are pictured above (with Jefferson’s engraving on top and Washington’s engraving on the bottom)[15]. Also pictured above is the original portrait by Antoine-Francois Callet, which is many times larger than the duplicate miniature engravings sent to Jefferson and Washington. According to Google Arts & Culture, the title of Callet’s color portrait is “Louis XVI, roi de France et de Navarre (1754-1793), revêtu du grand costume royal en 1779.” The work is the largest portrait of Louix XVI in Versailles.[16]

Robert Livingston’s request for instructions to Madison regarding portrait of Napoleon contained in valuable gold box:

In a letter[17] by Robert Livingston, former Minister to France, dated April 4, 1805 to Secretary of State James Madison, Livingston identified a portrait of Napoleon contained in a gold box “very richly set with diamonds of very considerable value.” Livingston viewed the portrait as a “parting” gift received five months after “[m]y mission having been so long closed.” Nevertheless, Livingston reported the item and deferred to Madison and Jefferson for instructions.

In Livingston’s view, he did not consider the gift “as falling within the prov<isions> of the constitution” because the letter had no reference to his “former official character.” Rather, the “new minister had been for five months in full possession of his office” and Livingston considered himself “a private man” holding “no place” under the United States.

Livingston wrote that he merely viewed the portrait as proof of Napoleon’s “personal good will.” Livingston conceded that, “should you or the President, view it in a different light I shall think myself bound” to abide by Madison and Jefferson’s judgment as follows:

My mission having been so long before closed, I viewed the gift as a parting one from the Emperor, intended as a proof of his personal good will, but should you or the president, view it in a different light I shall think myself bound to abide by his judgment, or yours, & in that case, I pray you to inform him that I shall hold it subject to his directions.

Note that Livingston also attached a copy of the original cover letter from Talleyrand stating that Napoleon had “charged him with delivering the accompanying portrait as a mark of Napoleon’s esteem, which would enable Livingston to carry to the United States this sign of Napoleon’s opinion of him….” Talleyrand appears to also have sent a separate collection of engraving for Livingston to place in a museum “to attest to Livingston’s interest in art and contribute to the education of American youth.” Livingston described the collection as “twenty four volumes in fol. of prints & a number of portfols. Containing paintings in oil and water colours, most of them copies from antiques & from Raphael; several views of Constantinople, Cairo, &c.” Importantly, Livingston’s letter and enclosures to Madison fully disclosed all gifts.

The five-month time frame cited by Livingston appears accurate. John Armstrong replaced Livingston as Minister to France on November 18, 1804. But additional research would be necessary to verify when Armstrong arrived in France. It is unclear what Madison and/or Jefferson decided after receipt of Livingston’s letter. It is also worth noting that Robert Livingston’s tenure as ambassador to France was enormously successful, having resulted in the Louisiana Purchase in 1803.

[1] The Life of Oliver Elsworth, William Garrott Brown (Macmillian Co., 1905) p. 308-309.

[2] The story is also told by Connecticut Chief Justice, Simeon E. Baldwin, in the book Great American Lawyers: A History of the Legal Profession in America (1907), vol. II, edited by William Draper Lewis, p. 128-129.

[3] Oeuvres de Comte P. L. Roederer, Pierre-Louise Roederer, vol. III, 337-338.

[4] Click here for a discussion of the Crime Act of 1790: https://statutesandstories.com/blog_html/crimes-act-of-1790-1st-federal-criminal-law/

[5] The first law providing for U.S. consuls was passed on April 14, 1792 and related to treaty obligations between the United States and France. According to the Office of the Historian, Department of State, U.S. consuls were not required to be U.S. citizens and did not receive a salary. They were often merchants with business connections in the city where they had been appointed. https://history.state.gov/about/faq/origin-of-consular-service

[6] https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/founding-fathers-north-carolina#davie

[7] Alexander DeConde, “The Role of William Vans Murray in the Peace Negotiations between France and the United States, 1800,” 15 Huntington Library Quarterly no. 2, p 186. (1952).

[8] Click here for a discussion of Swift’s prolific legal publications and career: https://statutesandstories.com/blog_html/laws-of-the-united-states-1796-folwell-swift/

[9]https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Signing_of_the_Treaty_of_Mortefontaine,_30th_September_1800_by_Victor-Jean_Adam.jpg

[10] “From George Washington to Charles Pinckney, 29 March 1791,” Founders Online, National Archives, version of January 18, 2019, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-08-02-0015 . [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 8, 22 March 1791 – 22 September 1791, ed. Mark A. Mastromarino. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1999, pp. 22–24.]

https://founders.archives.gov/?q=pinckney&s=2111311111&r=159

[11] “From George Washington to Edward Rutledge, 16 January 1791,” Founders Online, National Archives, version of January 18, 2019, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-07-02-0129 [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 7, 1 December 1790 – 21 March 1791, ed. Jack D. Warren, Jr. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1998, pp. 236–237.]

[12] “From George Washington to William Washington, 8 January 1791,” Founders Online, National Archives, version of January 18, 2019, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-07-02-0116 . [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 7, 1 December 1790 – 21 March 1791, ed. Jack D. Warren, Jr. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1998, pp. 211–213.]

[13] “From Thomas Jefferson to William Short, 24 January 1791,” Founders Online, National Archives, version of January 18, 2019, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-18-02-0197 [Original source: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 18, 4 November 1790 – 24 January 1791, ed. Julian P. Boyd. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1971, pp. 600–603.]

[14] As will be discussed in Part II of this memo, the Estates General was summoned by Louis XVI to meet at Versailles on May 5, 1789. This would be the first meeting of the Estates General in 175 years. On June 17, 1789, the Third Estate voted to establish the National Assembly, constituting the first act of revolution. The Tennis Court Oath would be taken three days later on June 20, 1789, when the National Assembly found themselves locked out of their meeting hall at Versailles. The following year, in June of 1791, King Louis XVI and his family would be arrested at Varennes, northeast of Paris, trying to escape to the Austrian Netherlands.

[15] The image on the left, the engraving delivered to Jefferson’s apartment in France, can be viewed at the Monticello website: https://www.monticello.org/site/research-and-collections/louis-xvi-engraving

The image on the right, the duplicate engraving delivered to Washington by Ambassador Jean-Baptiste chevalier de Ternant, can be viewed at the Mount Vernon website: https://www.mountvernon.org/preservation/collections-holdings/browse-the-museum-collections/object/w-767a-b/

[16] https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/louis-xvi-king-of-france-and-navarre-1754-1793-wearing-his-grand-royal-costume-in-1779/9gFrdyY6xDaHgw

[17] “To James Madison from Robert R. Livingston, 4 April 1805,” Founders Online, National Archives, version of January 18, 2019, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/02-09-02-0230 [Original source: The Papers of James Madison, Secretary of State Series, vol. 9, 1 February 1805–30 June 1805, ed. Mary A. Hackett, J. C. A. Stagg, Mary Parke Johnson, Anne Mandeville Colony, Angela Kreider, and Katherine E. Harbury. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2011, pp. 211–213.]