Revolutionary War Property Confiscation Acts, Hamilton’s Representation of Loyalists, Laying the Groundwork for Judicial Review

The Revolutionary War was not merely a struggle for independence. It was also a civil war between British loyalists (known as Tories) and American patriots (known as Republicans, Whigs or rebels). At different times during the war – as the British gained/lost territory – the control over hostile populations shifted from one side to another. This blog post will explore the use of loyalty oaths, property confiscation, banishment and parole as means of controlling occupied populations. Outrage over the continued use of these practices after the war resulted in the adoption of legal protections that are now enshrined in the U.S. Constitution, including prohibitions on ex post facto laws, bills of attainder, and seizure of property without due process of law.

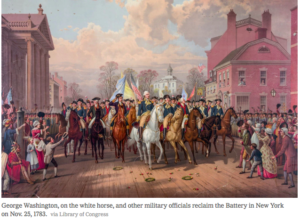

Bitter animosity between loyalists and patriots: The struggle between patriots and loyalists was particularly acute in New York and South Carolina, which changed hands during the war. Loyalist support was especially strong in New York, which served as a British base of operations. In fact, New York City was controlled by Britain until “Evacuation Day” in November of 1783, longer than any other American city. During British occupation it is estimated that more than 10,000 captured American prisoners died of disease or malnutrition on British prison ships anchored in New York’s East River. The only recently revealed story of the horrific conditions on the British prison barges is told by historian Robert Watson in The Ghost Ship of Brooklyn (2017).

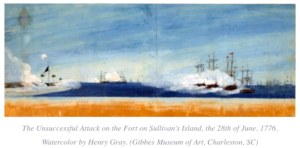

The British easily captured New York City in July of 1776 following the Battle of Brooklyn. Had Washington not escaped, the war could have ended early. That same month Charleston mounted a successful defense against the British navy. At the time, the British fleet had not lost a battle in over 100 years. The unexpected British defeat at Charleston in 1776 was one of the most decisive American victories of the war and provided a needed morale boost, at the same time that the colonies were declaring independence.

After taking New York, it is not difficult to understand why the British wanted to next control Charleston. As one of the richest colonial cities, it was full of wealth that could be plundered. As the busiest seaport in the South, Charleston was one of the largest colonial cities along with Philadelphia, New York, and Boston. For these reasons, the British would later return to capture Charleston in 1779, converting a rebel stronghold into a hostile, captive city. The British learned their lesson from their initial defeat in Charleston in 1776. In 1779, the British returned to Charleston with 10,000 troops to surround the city, including Hessians and Scottish Highlanders. When Charleston surrendered in 1780 approximately 6,000 American soldiers and 1,000 sailors became prisoners in the largest single American defeat of the war. Over the course of their captivity more than 45% of the American prisoners of war died. These wartime losses generated bitter resentment against British loyalists.

Before Charleston was fully surrounded by British forces, the South Carolina Legislature fled the city. The Legislature’s last act granted Governor Rutledge near-dictatorial authority to govern as he saw fit. The “Ordinance for the Better Defense and Security of the State During the Recess of the General Assembly” is copied below. The Act concentrated power in the hands of Governor Rutledge during a time of “danger and invasion” by a “tyrannical” and “cruel enemy.”

The British “Southern Strategy” involved “Americanizing” the war in the South and ferocious scorched earth campaigns in loyalist backcountry strongholds. These tactics resulted in greater hardship and more battles in South Carolina (400) than in any other state. General Nathanael Green (“the Savior of the South” also known as the “Fighting Quaker”) and Francis Marion (the “Swamp Fox”) earned their nicknames in South Carolina where the bitterly fought battles of Kings Mountain and Cowpens would later help turn the tide of the war.

South Carolina’s Anti-Loyalist Confiscatory and Ameration Acts: After the fall of Charleston in 1780, the South Carolina Legislature reassembled in Jacksonborough, approximately 30 miles from British-occupied Charleston. The Jacksonborough Assembly adopted the punitive Confiscation and Amercement Acts. Whether motivated by revenge, or desperation based on financial necessity, the Acts permitted Governor Rutledge to banish Loyalists, confiscate their property, and assess financial penalties (Amercement) on those who’s varying degrees of British loyalty did not warrant full confiscation. In fact, all states passed some version of a “confiscation law.” These punitive confiscation laws effectively criminalized disloyalty and political dissent.

Indeed, the Continental Congress had authorized the confiscation of loyalist property in 1777. The anti-loyalist Resolution recommended that the states confiscate and sell all real and personal property of loyalists “who have forfeited same and the right to the protection of their respective states” to be invested in the war effort. Click here for a link to the Journals of the Continental Congress.

The South Carolina Confiscation Act was a bill of attainder that divided loyalists into the following six categories of culpability:

CLASS I – Comprehends all British subjects who have property in this country, that is to say, such persons as never have submitted to the American Government.

CLASS II – Such of the former inhabitants of this Country, as presented congratulatory addresses to Sir Henry Clinton and Admiral Arbuthnot

CLASS III – Those who petitioned to be armed in defence of the British Government, after the conquest of this Province

CLASS IV – Those who congratulated Earl Cornwallis, on the victory gained at Camden

CLASS V – Those who have borne commissions, civil or military, under the British Government, since the conquest of this Province

CLASS VI – Obnoxious Persons

A separate Amercement Act required others who accepted British “protection” during the war to pay a twelve percent fine. Yet, by 1787 approximately two-thirds of defendants facing confiscation, banishment, or other penalties had received reduced fines or permission to continue residing in the state.

New York’s Anti-Loyalist laws: In 1776 when the British occupied New York City they confiscated the estates of patriots who had fled the city. Beginning in March of 1777, New York’s Provincial Convention returned the favor and created “Committees of Sequestration” to seize and auction off property abandoned by Loyalists. In October of 1779, New York adopted an aggressive confiscation law which was formally known as “An Act for the Forfeiture and Sale of the Estates of Persons who have adhered to the Enemies of this State, and for declaring the Sovereignty of the People of this State, in respect to all Property within the same.” Otherwise known as the “Forfeiture Act” (New York Laws, 3rd session, Ch. 25), the Act listed New Yorkerers who had remained loyal to the King. These “offenders” were banished and forfeited their property rights. The state was empowered to seize and sell forfeited property. “Commissioners of Forfeiture” were appointed to carry out the Act.

In 1782, New York’s punitive “Citation Act” made it difficult for British creditors to collect money from American debtors. Hamilton was particularly appalled by the “Trespass Act” of 1783 which allowed patriots who had left property behind British lines to arbitrarily sue anyone who occupied, damaged or destroyed the abandoned property. Additional laws barred loyalists from certain professions, imposed oppressive taxes on them and deprived them of civil rights.

Alexander Hamilton’s defense of Loyalists: Despite the fact that doing so was politically unpopular, Alexander Hamilton did not shy away from representing loyalists seeking to reclaim seized property. Hamilton no doubt understood that many of his loyalist clients were very wealthy. Hamilton may also have believed these families, and their financial capital, would prove critical for re-building the United States after the war. He also wisely wanted to facilitate post war re-integration within American society. Hamilton correctly recognized that peacefully resolving property disputes was an important step in enabling a successful transition from violent revolution to civil society and the rule of law.

As described by historian Ron Chernow, Hamilton “thought America’s character would be defined by how it treated its vanquished enemies, and he wanted to graduate from bitter wartime grievances to the forgiving posture of peace.” In Hamilton’s view, New York’s anti-Tory legislation violated America’s peace treaty with Britain. Article V of the Treaty of Paris provided that Congress would “earnestly recommend” to state legislatures that restitution be made for seized Tory property. Article VI protected loyalists from future confiscations and promised that all jailed loyalists would be freed. The discriminatory treatment of Tories “sensitized Hamilton to the extraordinary danger of allowing state laws to supersede national treaties, making manifest the need for a Constitution that would be the supreme law of the land.” Click here for a link to Chernow’s biography of Alexander Hamilton.

In his “Letter from Phocion to the Considerate Citizens of New-York On the Politics of the Day” published in New York newspapers in 1784, Hamilton wrote that as a revolutionary war veteran he had “too deep a share in the common exertions of this revolution to be willing to see its fruits blasted by violence of rash and unprincipled men, without at least protesting their designs.” Invoking Plutarch and the Athenian soldier Phocion, Hamilton assailed the malignant precedent that would be set if the legislature was permitted to exile an entire class of of citizens without trials or hearings. In such event, “no man can be safe, nor know when he may be the innocent victim of a prevailing faction. The name of liberty applied to such a government would be a mockery of common sense.”

In his “Second Letter from Phocion” Hamilton wrote that “The world has its eye on America.” Hamilton asserted that if America acted wisely it had a historic opportunity to counter the skeptics of democracy and defeat despots everywhere by protecting individual rights.

In the course of three years Hamilton handled forty-five cases on behalf of Tory clients under the New York Trespass Act and another twenty cases under the Confiscation and Citation Acts. In 1784, Hamilton defended a Tory businessman, Joshua Waddington, in an important case that litigated the principle of judicial review.

The plaintiff, Elizabeth Rutgers, was a sympathetic widow who had fled British occupied New York and abandoned her family’s brewery and alehouse on Maiden Lane. The property was vandalized of everything of value by the British. Two years later Joshua Waddington spent several hundred pounds to restore and reopen the business. For the majority of the time that the business was operating, Waddington paid rent to the British. At the conclusion of the war in 1783, two days before a victorious Washington entered New York, a fire destroyed the brewery. When the dust settled, the prior owner, Elizabeth Rutgers, filed suit under the Trespass Act for back rent.

In the case of Rutgers v. Waddington Hamilton successfully argued that the Trespass Act violated both the law of nations and the Treaty of Paris, which had been ratified by Congress. The case established the principle that state legislation that conflicted with a United States treaty was void. In so holding the Rutgers case created an important state court precedent for judicial review, which was later expounded by Justice Marshall in the case of Marbury v. Madison. Hamilton subsequently made the same arguments for judicial review from the Rutgers case in Federalist 22 and 78. According to Hamilton, the “interpretation of the laws is the proper and peculiar province of the Courts” and in the case of conflict “the Constitution ought to be preferred to the statute.”

Epilogue: The Treaty of Paris attempted to restore property confiscated from Loyalists. The heirs of William Penn in Pennsylvania and George Calvert in Maryland are examples of loyalists who received substantial settlements. To the extent that large loyalist estates were parceled out into smaller plots in New York and the Carolinas, the confiscations resulted in a redistribution of wealth and land for individual yeoman farmers. Approximately 100,000 loyalists left United States during or after the Revolutionary War. Examples included, ironically, Benjamin Franklin’s son, William Franklin, and John Singleton Copley, arguably one of the greatest American painters of the time. William Franklin served as the Royal Governor of New Jersey until his arrest in 1776. Franklin became estranged from his father and fled to England after he was released in 1778. George Washington’s mother and several of his cousins were Tories. Both John Adams and John Hancock had in-laws who were loyalists. Substantial numbers of loyalists resettled in Canada, returned to Britain, or made new homes in the British colonies in the Caribbean.

Historian Rebecca Brannon suggests that South Carolina ultimately offered the most generous reconciliation for loyalists. In From Revolution to Reunion: The Reintegration of South Carolina Loyalists, Brannon argues that the very brutality and destruction suffered during the war convinced South Carolinians to seek reconciliation rather than retribution. Brannon also notes that a waiting period built into South Carolina’s Confiscation Act provided an opportunity for many loyalists to “petition or even pester” the General Assembly into reducing or waving excessive penalties.

In sum, the controversy and abuses precipitated by the arbitrary Confiscation Acts in the 1780’s provided valuable lessons. At the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia the founding fathers built important protections into the Constitution. Today, Article I, Section 9 of the Constitution prohibits ex post facto laws and bills of attainder, which were used by the former colonies against persecuted British loyalists.

Additional reading:

Nathanael Green in South Carolina: Hero of the American Revolution, Leigh Moring (2016)

Scars of Independence: America’s Violent Birth, Holger Hoock (2017)

The ”Havoc of War” and its Aftermath in Revolutionary South Carolina, Jerome Nadelhaft

The History of South Carolina, Snowden Yates (1920)

Rutgers v. Waddington (Historical Society of the New York Courts)

Rutgers v. Waddington: Alexander Hamilton, the End of the War for Independence, and the Origins of Judicial Review (Peter Charles Hoffer, 2016)

The Legislation for the Confiscation of British and Loyalist Property During the Revolutionary War, Rolfe Lyman Allen (1937)

Why the British Lost the Battle of Sullivan’s Island, Journal of the American Revolution (9/5/2016)

South Carolina Confiscation Act of 1782

South Carolina Ameration Act of 1782

South Carolina Oath Act of 1778

Examples of Confiscation Acts in Virginia: