Indian Non-Intercourse Acts and the Treaty of New York

First Congress, Ch. XXXIII, July 22, 1790, 1 Stat. 137; Second Congress, Ch. XIX, March 1, 1793, 1 Stat. 329; Third Congress, Ch. XXX, May 19, 1796, 1 Stat 469; 5th Congress, Ch. XXX, March 3, 1799, 1 Stat. 743, Seventh Congress, Ch. XXX, March 30, 1802, 2 Stat 139; Twenty-Third Congress, Ch. CLXI, June 30, 1834, 4 Stat. 729

Starting in the year 1790, the First Congress attempted in vain to protect the rights of Native American tribes. From 1790 to 1834, six Non-Intercourse Acts, also known as Indian Intercourse Acts, were passed by Congress in 1790, 1793, 1796, 1799, 1802, and 1834. The Acts regulated commerce with Native American tribes and sought to prevent the purchase of Native American lands without the approval of the federal government. The Acts generally required renewal every four years until the 1802 Act.

In particular, the Non-Intercourse Act of 1796 attempted to establish clear boundaries of Native American reservations and otherwise addressed legal rights, protections and commerce with Native American tribes. The principal provisions of the Indian Non-Intercourse Act of 1796 are set forth below:

Established boundaries between the U.S. and Indian tribes.

Prohibited settlers from hunting or driving livestock onto Indian lands, punishable by a fine of $100 or six months imprisonment.

Prohibited surveying or settling on Indian lands, punishable by a fine of $1,000 or 1 year imprisonment.

Required issuance of passports before traveling onto Indian country, punishable by a $50 fine or three months imprisonment.

Required licensing of tribal traders who were permitted to trade on tribal land.

Prohibited purchase of Indian lands, except as permitted by treaty.

Established penalties for committing crimes against “friendly Indians.” Provided for payment from the U.S. Treasury if the guilty American citizen was unable to afford restitution, but denied restitution from the U.S. Treasury if an Indian victim had sought private revenge or attempted to obtain satisfaction by force or violence.

Provided for Indian agents to live among the friendly tribes to secure the continuation of “their friendship” and to furnish them with useful domestic animals, implements of husbandry, goods and money, not exceeding $15,000 per year.

Click here for a link to John Adams’ copy of the Non-Intercourse Act of 1796.

The Non-Intercourse Act of 1796 was passed after President Washington asked Congress in his 7th Annual Address to strengthen the prior Non-Intercourse Acts which had proven inadequate.

Washington’s Seventh Annual Address to Congress of 1795: In his 7th Annual Address, Washington sought Congressional action to protect Native Americans from injustices at the hands of “the lawless part of our frontier inhabitants”:

While we indulge the satisfaction which the actual condition of our Western borders so well authorizes, it is necessary that we should not lose sight of an important truth which continually receives new confirmations, namely, that the provisions heretofore made with a view to the protection of the Indians from the violences of the lawless part of our frontier inhabitants are insufficient. It is demonstrated that these violences can now be perpetrated with impunity, and it can need no argument to prove that unless the murdering of Indians can be restrained by bringing the murderers to condign punishment, all the exertions of the Government to prevent destructive retaliations by the Indians will prove fruitless and all our present agreeable prospects illusory. The frequent destruction of innocent women and children, who are chiefly the victims of retaliation, must continue to shock humanity, and an enormous expense to drain the Treasury of the Union.

To enforce upon the Indians the observance of justice it is indispensable that there shall be competent means of rendering justice to them. If these means can be devised by the wisdom of Congress, and especially if there can be added an adequate provision for supplying the necessities of the Indians on reasonable terms (a measure the mention of which I the more readily repeat, as in all the conferences with them they urge it with solicitude), I should not hesitate to entertain a strong hope of rendering our tranquillity permanent. I add with pleasure that the probability even of their civilization is not diminished by the experiments which have been thus far made under the auspices of Government. The accomplishment of this work, if practicable, will reflect undecaying luster on our national character and administer the most grateful consolations that virtuous minds can know.

Click here for a link to Washington’s Seventh Annual Address to Congress of 1795.

Background: According to historian Joseph Ellis, the American victory in the Revolutionary War was a stunning defeat for Britain, but an “unmitigated calamity” for the roughly 100,000 Native Americans living between the Appalachians and the Mississippi River. As described by Ellis in American Creation: Triumphs and Tragedies at the Founding of the Republic, the American victory “triggered a tidal wave of western migration of settlers who understood ‘pursuit of happiness’ to mean owning their own land.” Ultimately, “Indian Country” would be overwhelmed demographically by western settlers notwithstanding the fact that the “principal founders acknowledged that the indigenous people of North America had a legitimate claim to the soil and a moral claim on the conscience of the infant republic.”

When the Constitution was drafted in 1787 it granted the new federal government the exclusive authority to negotiate with the “Indian Tribes.” President Washington, Secretary of War Henry Knox, and Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson agreed that Indian policy was a responsibility of the federal government.

In a letter to Washington Knox explained that “the independent tribes of indians ought to be considered as foreign nations, not as the subjects of a particular state.” Conceptually, Knox and Washington respected the underlying rights of Native Americas as sovereign nations to their lands. As described by Knox, “Indians being the prior occupants of the rights of the soil…To dispossess them…would be a gross violation of the fundamental Laws of Nature and of that distributive Justice which is the glory of a nation.”

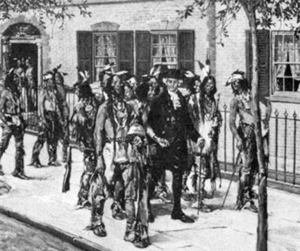

Treaty of New York: The first treaty entered into by the new federal government was the Treaty of New York with the Creek (Muscogee) Nation of Indians. The treaty was negotiated by Henry Knox and Chief Alexander McGillivray (who had mixed Creek and Scottish parentage). After the treaty was negotiated, twenty-eight chiefs of the Creek nation came to New York in August of 1790 for the treaty signing and a tour of New York City. President Washington’s Proclamation of August 14, 1790 required “all officers of the United States, civil and military, and all other citizens and inhabitants thereof, faithfully to observe and fulfil the same.”

Concerned over chaos on the frontier and recognizing that the federal government had few resources for reducing hostilities, Washington and Knox decided to recognize Indian title to tribal lands. Washington and Knox hoped that the Indians could be “civilized” to adopt an agricultural way of life and abandon communal landownership and seasonal migration. Under the assimilation policy, “useful domestic animals and implements of husbandry” would be provided to the tribe to encourage them to become “herdsman and cultivators” instead of “remaining in a state as hunters.”

The engraving below appeared in Harper’s Magazine in 1899 and depicts George Washington escorting Creek Chiefs on Broadway in New York. Also shown are two sketches of Creek Chiefs by John Trumbull in July of 1790, which were made “by stealth” since the Creek were unwilling to agree to a formal sitting. Secretary of War Henry Knox’s portrait was made by Gilbert Stuart in 1806.

On December 29, 1790, Washington addressed the Seneca Tribe of New York, following the passage of the first Non-Intercourse Act:

I the President of the United States, by my own mouth, and by a written Speech signed with my own hand [and sealed with the Seal of the U S] Speak to the Seneka Nation, and desire their attention, and that they would keep this Speech in remembrance of the friendship of the United States.

I have received your Speech with satisfaction, as a proof of your confidence in the justice of the United States, and I have attentively examined the several objects which you have laid before me, whether delivered by your Chiefs at Tioga point in the last month to Colonel Pickering, or laid before me in the present month by the Cornplanter and the other Seneca Chiefs now in Philadelphia.

In the first place I observe to you, and I request it may sink deep in your minds, that it is my desire, and the desire of the United States that all the miseries of the late war should be forgotten and buried forever. That in future the United States and the six Nations should be truly brothers, promoting each other’s prosperity by acts of mutual friendship and justice.

I am not uninformed that the six Nations have been led into some difficulties with respect to the sale of their lands since the peace. But I must inform you that these evils arose before the present government of the United States was established, when the separate States and individuals under their authority, undertook to treat with the Indian tribes respecting the sale of their lands.

But the case is now entirely altered. The general Government only has the power, to treat with the Indian Nations, and any treaty formed and held without its authority will not be binding.

Here then is the security for the remainder of your lands. No State nor person can purchase your lands, unless at some public treaty held under the authority of the United States. The general government will never consent to your being defrauded. But it will protect you in all your just rights.

Hear well, and let it be heard by every person in your Nation, That the President of the United States declares, that the general government considers itself bound to protect you in all the lands secured you…

Click here for a link to Washington’s famous address to the Seneca Indians.

This underlying concern for preserving Native American rights to their tribal lands dates back to King George III’s Proclamation of 1763 following the conclusion of the French and Indian War/Seven Years’ War. This intent to protect Native American rights was reaffirmed in the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 which provided as follows in Article 3:

The utmost good faith shall always be observed towards the Indians; their lands and property shall never be taken from them without their consent; and, in their property, rights, and liberty, they shall never be invaded or disturbed, unless in just and lawful wars authorized by Congress; but laws founded in justice and humanity, shall from time to time be made for preventing wrongs being done to them, and for preserving peace and friendship with them.

Additional reading:

The Chief of State and the Chief (American Heritage Magazine)