FIRST FEDERAL MILITARY PENSIONS

The first federal pension laws were adopted during the Revolutionary War in 1776. Enacted on August 26, 1776, the first federal pension act provided disability pensions for soldiers and sailors injured in service of the colonies. The Act granted half pay for life in cases of loss of limb or other serious disability, which prevented the veteran from earning a living. The half pay was intended to continue for the duration of the disability.

Within the next two years pension rights would be expanded by the Continental Congress which simultaneously attempted to encourage military enlistment while limiting desertion.

General Washington was a strong proponent of “half pay and pensionary establishment.” During the harsh winter at Valley Forge, he sent Congress a troubling account on January 28, 1778.

Washington explained that the requested half pay pension would “not only dispel the apprehension of personal distress at the termination of the war, from having thrown themselves out of professions and employments they might not have the power to resume; but in a great degree relieve the painful anticipation of leaving their widows and orphans, a burthen on the charity of their country, should it be their lot to fall in its defense.”

Following Washington’s report and appeal for action, the Continental Congress unanimously voted on May 15, 1778 for a half pay pension for all commissioned officers who continued in the service of the United States through the end of the war. Journals of Congress, ii, 554-555. In 1780 a resolution was adopted extending half pay to widows and orphan children of officers killed in action.

Yet, because the Continental Congress did not have the authority or the funds to make the pension payments, the actual distributions were left the individual states, with varying success.

Ultimately, compliance with their revolutionary pension obligations depended on the individual state. It is believed that only 3,000 Revolutionary War veterans received pensions. Subsequently, grants of public land were issued to those who served through the end of the war.

By way of example, in 1779 the Continental Congress authorized a lifetime disability pension for Margaret Corbin, who was injured while helping her husband during the defense of Fort Washington. The Resolution explains:

“That Margaret Corbin, who was wounded and disabled in the attack on Fort Washington, whilst she heroically filled the post of her husband who was killed by her side serving a piece of artillery, do receive, during her natural life, or the continuance of the said disability, the one-half of the monthly pay drawn by a soldier in the service of these states; and that she now receive out of the public stores, one complete suit of cloaths [sic], or the value thereof in money.” 14 Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, at 805 (Worthington Chauncey Ford, ed., 1909).

Status at the end of the Revolutionary War in 1783

In 1783, David had defeated Goliath. The end of the Revolutionary War was a time to celebrate the United States’ victory over Great Britain. Yet, the disbanding of the heroic Continental Army presented a bittersweet story, as described by historian Joseph Ellis:

At least in retrospect, the dissolution of the Continental Army in the spring of 1783 was one of the most poignant scenes in American history, as the men who had stayed the course and won the war were ushered off without pay, with paper pensions and only grudging recognition of their service. Washington could only weep: “To be disbanded. . . like a set of beggars, needy, distressed, and without prospect. . . will drive every man of Honor and Sensibility to the extreme Horrors of Despair.” Click here for a link to Washington’s letter of April 4, 1783 to Theodorick Bland.

Unfortunately, the Confederation Congress under the Articles of Confederation lacked the resources to comply with the nation’s mounting war debts, let alone unpaid pension obligations.

Morris Notes

As recognized by the Robert Morris, the de facto Treasurer of the United States in 1783, the nation’s financial situation was “desperate.” Upon resigning as Superintendent of Finance under the Article of Confederation, Robert Morris explained to George Washington that, “I hope my successor will be more fortunate than I have been and that our Glorious Revolution may be crowned by those Act of Justice, without which the greatest human Glory is but the Shadow of Shade.” Click here for a link to Robert Morris’ February 27, 1783 letter to Washington.

Lacking any governmental funds, Morris spent his last days in office personally writing checks to all members of the army three months of salary. The so called “Morris notes” nearly bankrupted Morris, who was one of America’s richest men at the time. When Morris announced his intention to resign from his thankless job, he explained that “I will never be the Minister of Injustice.”

As summarized by Morris, he sincerely believed “that a great Majority of the Members of Congress wish to do Justice But I as sincerely believe that they will not adopt the necessary Measures because they are afraid of offending their States.” Morris observed that “From my Soul I pity the Army, and you my dear Sir in particular, who must see and feel for their Distresses without the Power of relieving them.”

Pensions under the new federal government

In 1789, after the adoption of the U.S. Constitution, the first Congress assumed the unmet burden of paying veterans benefits. The first federal pension law passed by Congress recognized that the new federal government would be responsible for paying the unmet disability pensions promised by the Continental Congress and the states. Act of July 16, 1790, ch. 27, § 1, 1 Stat. 95. Click here for a copy of the John Adams’ copy of the Invalid Pension Act, Chapter XXVII, of the Second Session of the First Congress. Interestingly, the famous compromise providing for the establishment of a future federal capital in Washington, D.C., was also adopted on July 16, 1790.

Arguably, Revolutionary War veterans, including Alexander Hamilton, were among the strongest supporters of the new Constitution because they understood that a strong central government was necessary to backstop the national pension obligation. Successive annual appropriations would be required because Congress only accepted financial responsibility on an annual basis.

By 1816 the pension rolls numbered 2,200 pensioners. Due to the growing cost of living and a surplus in the Treasury, in 1816 Congress raised payments for all disabled veterans and granted half-pay pensions for five years to widows and orphans of soldiers of the War of 1812.

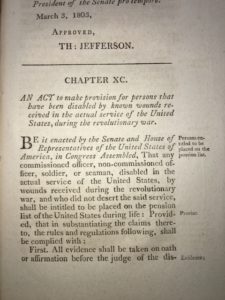

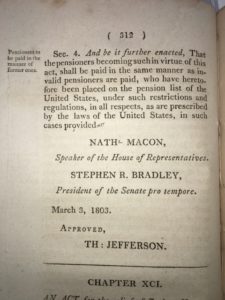

Pictured Chapter XC, Acts of 1803, which provided for payment of pensions through the Department of War, after each case was reviewed by a federal judge.