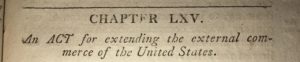

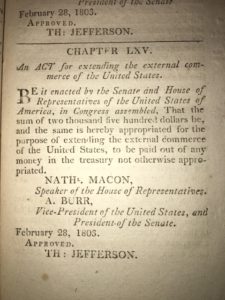

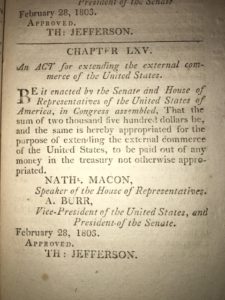

An Act for Extending the External Commerce of the United States (Congress secretly authorizes funds for the Lewis and Clark Expedition)

[Chapter LXV, Seventh Congress, Second Session, Feb. 19, 1803]

On January 18, 1803, President Thomas Jefferson sent a confidential message to Congress requesting the appropriation of $2,500 “for the purpose of extending the external commerce of the United States.” While Jefferson’s description of the proposed Act was purposely vague, Jefferson’s purpose was to fund what would later be known as the Lewis & Clark expedition.

In his request to Congress Jefferson explained that:

An intelligent officer, with ten or twelve chosen men, fit for the enterprise, and willing to undertake it, taken from our posts, where they may be spared without inconvenience, might explore the whole line, even to the Western Ocean, have conferences with the natives on the subject of commercial intercourse, get admission among them for our traders, as others are admitted, agree on convenient deposits for an interchange of articles, and return with the information acquired, in the course of two summers.

According to Jefferson, secrecy was required to prevent “obstructions” by otherwise “interested” parties. He explained that an Act appropriating funds for the cryptic “purpose of extending the external commerce of the United States” would “cover the undertaking from notice.” He reasoned that the “interests of commerced” justified the expedition which would also advance the “geographical knowledge of our own continent.”

According to Jefferson, secrecy was required to prevent “obstructions” by otherwise “interested” parties. He explained that an Act appropriating funds for the cryptic “purpose of extending the external commerce of the United States” would “cover the undertaking from notice.” He reasoned that the “interests of commerced” justified the expedition which would also advance the “geographical knowledge of our own continent.”

In his January 18 letter Jefferson explained that:

The interests of commerce place the principal object within the constitutional powers and care of Congress, and that it should incidentally advance the geographical knowledge of our own continent, cannot be but an additional gratification.

A week earlier, on January 11, 1803 President Jefferson nominated “Robert Livingston to be Minister Plenipotentiary, and James Monroe to be Minister Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary, to enter into a treaty or convention with the First Consul of France, for the purpose of enlarging, and more effectually securing, our rights and interests in the river Mississippi, and in the territories eastward thereof.”

Historian Stephen Ambrose recounts that Jefferson learned in the spring of 1801 that the Louisiana territory had been transferred from Spain to France. This development was highly problematic for Jefferson who wrote that “There is on the globe one single spot, the possessor of which is our natural and habitual enemy. It is New Orleans, through which the produce of three eights of our territory pass to market.” Click here for a link to Undaunted Courage: Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West (Ambrose 1996).

Historian Stephen Ambrose recounts that Jefferson learned in the spring of 1801 that the Louisiana territory had been transferred from Spain to France. This development was highly problematic for Jefferson who wrote that “There is on the globe one single spot, the possessor of which is our natural and habitual enemy. It is New Orleans, through which the produce of three eights of our territory pass to market.” Click here for a link to Undaunted Courage: Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West (Ambrose 1996).

As long as New Orleans (and control of the Mississippi River) was under the control of the receding Spanish empire, tensions with the United States could be avoided. An expansionistic French empire under an aggressive Napoléon Bonaparte was another story.

Unlike Spain, Napoleon had global ambitious and was planning rebuild an empire in the western hemisphere. For this reason, Jefferson warned that “The day that France takes possession of New Orleans…we must marry ourselves to the British fleet and nation.”

France had controlled the vast Louisiana Territory from 1699 until 1762, when it transferred the territory to its ally Spain near the end of the French and Indian War. Thirty years later, Napoleon reclaimed the territory with the secret Treaty of San Ildefonso in 1800. When Jefferson learned that the territory had retroceded to France, he opined that “this little event, of France possessing herself of Louisiana, … is the embryo of a tornado which will burst on the countries on both shores of the Atlantic and involve in it’s effects their highest destinies.” Jefferson letter of April 25, 1802 to Pierre Samuel De Don’t de Nemours.

Even though he had lived in Paris for five years while serving as America’s first ambassador to France, Jefferson bluntly notified Napoleon that the United States would consider any attempt to land French troops in Louisiana a cause for war.

Napoleon knew that he needed funding for a pending war with Britain. Napoleon was also frustrated by a successful revolt in Haiti. Both considerations led Napoleon to abandon his aspirations for the Louisiana territory. Napoleon’s sudden change of heart was nothing less than a seismic shift for the United States, which was particularly worried that France would restrict access to the important port of New Orleans, which could severely impede American commerce along the Mississippi River.

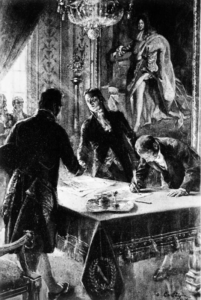

Originally, President Jefferson only proposed to purchase New Orleans from France. The American minister to France, Robert Livingston, had authority to spend $10,000,000. When Secretary of State James Monroe arrived to join Livingston in April of 1803, he was astonished to learn that Napoleon was offering the entire Louisiana Territory for $15,000,000. Rather than waiting for additional permission, on April 30, 1803 Livingston and Monroe promptly agreed. It mattered not that the vast territory was largely uncharted or that its western and northern borders were largely undefined. Jefferson publicly announced the agreement on July 4, the 27th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence.

Despite his strict constructionist philosophy – to President Jefferson’s credit – he recognized that Napoleon’s offer to sell the entire Louisiana Territory was an offer too good to to refuse. Eight months after the funds for the Lewis and Clark expedition were quietly appropriated in January of 1803, the Senate eventually approved the Louisiana Purchase treaty on October 31, 1803.

Legacy of the Louisiana Purchase and the Lexis and Clark Expedition: The Louisiana Purchase doubled the size of the United States, adding 828,000,000 square miles of territory at a cost of 3 cents per acre. The extensive Louisiana Territory extended westward from the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains and we bounded from the Gulf of Mexico to the Canadian border. Fifteen states would be eventually created from in a deal that is arguably one of the most important legacies of Jefferson’s presidency.

According to Joseph Ellis, the Louisiana Purchase was, politically, “the most consequential executive decision in American history.” Ellis explains that one of the great ironies of American history was the fact that the Louisiana Purchase was conducted by Jefferson, an anti-federalist who was on record “against energetic protection of executive power.” In one fell swoop, Jefferson removed all British and French imperial ambitions in North America. Click here for a link to American Creation: Triumphs and Tragedies at the Founding of the Republic (Ellis 2007).

Jefferson considered seeking a constitutional amendment, but he knew that he needed to seize the opportunity before Napoleon changed his mind. While Jefferson was conflicted, he justified the purchase as lawful based on the express power to enter into treaties and other implied powers. Jefferson also knew that the purchase would be popular for the upcoming presidential election of 1804.

The treaty was finalized on April 30 and signed on May 2. The Senate ratified the treaty in October. France formally transferred authority over the territory in December 1803. Exactly nine years after the Louisiana Purchase agreement was made, Louisiana (the 18th state) became the first state admitted into the United States from the Louisiana Territory, on April 30, 1812.

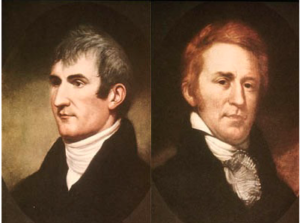

Jefferson selected his private secretary, Meriwether Lewis, to lead the expedition. Lewis was a U.S. army captain who spent months studying with Jefferson to prepare for the mission. Jefferson’s instructions to Meriwether Lewis (June 20, 1803). As described by Steven Ambrose, to prepare for the trip Jefferson provided Lewis with an undergraduate level education at Monticello a diverse range of topics, including North American geography, botany, mineralogy, astronomy, and ethnology. Lewis was well suited for the job because of his “firmness of constitution & character, prudence, habits adapted to the woods & a familiarity with the Indian manners & character, requisite for this undertaking.”

Background: In his first inaugural address in 1801 Jefferson envisioned, “A rising nation, spread over a wide and fruitful land, advancing rapidly to destinies beyond the reach of mortal eye.”

Jefferson’s interest in exploring the west dated back a half century to his father, who had been, among other things, a surveyor and member of the Loyal Land Company, which had been awarded 800,000 acres west of the Appalachian Mountains.

Additional reading and resources:

Jefferson’s confidential letter to Congress (Monticello)

Jefferson Exhibits and Lewis and Clarke Expedition (Library of Congress)

Louisiana Purchase (Library of Congress)

Jefferson’s 1/28/03 confidential letter to Congress (Library of Congress)

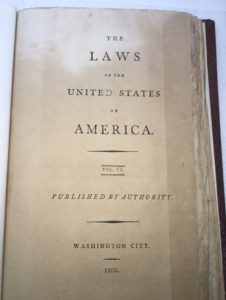

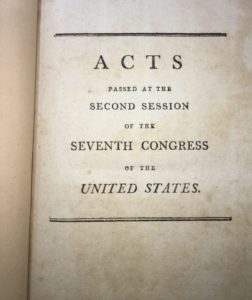

Pictured below are original copies of both the “slip” and bound versions of the laws of the Seventh Congress.

While the soft cover “slip” version of the Acts only contains a single session of Congress, the bound version generally contains both sessions.