Madison and the Bill of Rights (Part II)

This post is the second in a three-part series about James Madison and the Bill of Rights. This post (Part II) tells the story of the Constitutional Convention of 1787, which curiously decided not to include a bill of rights with the Constitution. John Adams opined that the new Constitution was, “if not the greatest exertion of human understanding, the greatest single effort of national deliberation that the world has ever seen.” If Adams is correct, how did the Federalists defend this glaring omission?

With hindsight, modern audiences readily agree with the Anti-Federalists, who advocated for the adoption of a Bill of Rights. The Constitution was ratified in 1788, but only after intense debates at the state ratifying conventions. During the difficult ratification process in Virginia, James Madison would come to recognize the failure of the Constitutional Convention to include a bill of rights. Madison rectified this error at the first Congress by preparing what would become the Bill of Rights.

When the idea of a federal Bill of Rights was first proposed at the Constitutional Convention in 1787, the vast majority of the founders disagreed. At the time, eight state constitutions already included bills of rights. Roger Sherman of Connecticut thought that this was sufficient since the new federal Constitution did not repeal these state protections. In Federalist 84, Alexander Hamilton warned that a federal bill of rights would be dangerous to liberties that weren’t enumerated.

Madison originally argued that a bill of rights wasn’t necessary because “the government can only exert the powers specified by the Constitution.” Ultimately, Madison was persuaded of the wisdom of the so-called Massachusetts Compromise. Beginning with Massachusetts, several large states with powerful Anti-Federalists constituencies agreed to ratify the Constitution based on the assurance that a bill of rights would be adopted by the first Congress. Madison’s conversion to support a bill of rights was also motivated by campaign promises that he was forced to make in Virginia when he ran for election to the first Congress.

Anti-Federalist Patrick Henry denied Madison appointment to the Senate from Virginia. Madison was forced to run against James Monroe in a Congressional district gerrymandered against him. During this hard-fought campaign during the winter of 1788-1789, Madison put his honor on the line by making a public pledge that, if elected, he would work for the adoption of a bill of rights at the first Congress. Writing from Paris, Thomas Jefferson also prevailed upon Madison that “no just government” should refuse to adopt a Bill of Rights.

Historian Paul Finkelman observes that “Madison’s paternity of the Bill of Rights was a reluctant one that he accepted only after political realities forced him to rethink long-held positions.” For Finkelman, Madison’s primary purpose in supporting the Bill of Rights was two-fold, “to fulfill promises made to his constituents during his campaign for Congress and to undermine the opposition to the Constitution.” Madison admitted as much when he introduced the draft on June 8, 1789. For Madison the proposed Bill of Rights would not only “stifle the voice of complaint,” but also make “friends of many who doubted the merits of the constitution.”

Part I of this post discusses declarations of rights in Anglo-American history and the evolution of the political philosophy of natural rights. These concepts were put into action during the American Revolution. Beginning with the Virginia Declaration of Rights in 1776 individual rights were codified in new state constitutions, building on legal authorities dating back to the Magna Carta.

Part III (pending) completes the story of how Madison drafted the Bill of Rights during the first Congress. Madison focused on individual liberties which he “limited to points which are important in the eyes of many and can be objectionable in those of none.” In so doing he preserved the structural integrity of the Constitutional framework, without making any substantive amendments to the body of the Constitution sought by the Anti-Federalists. Madison then relentlessly shepherded his Amendments through the first Congress.

Constitutional Convention declines to add a Bill of Rights

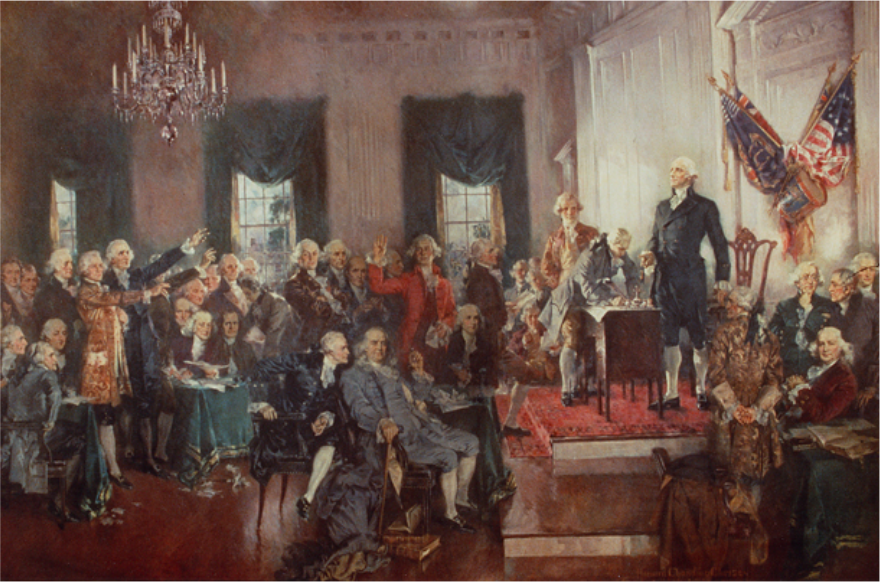

The Constitutional Convention met between May and September of 1787 in Philadelphia’s Independence Hall. During the long, hot, but productive summer the delegates hashed out several innovative compromises that established the longest continuously operating constitution in history. Click here for a link to a discussion of the Constitutional Convention and what many historians have described as America’s Second Revolution. The framers’ primary objective was to establish a new form of government, replacing the increasingly ineffective Article of Confederation. Yet, codifying protections for individual liberties into the Constitution was not high on their agenda.

According to historian Joseph Ellis, over the course of the ratification debate, it became “abundantly clear that the biggest mistake made by the delegates at the Constitutional Convention had been to omit a bill of rights from the final draft of the document.” Chronicler of the Constitutional Convention and author of the book Miracle at Philadelphia, historian Catherine Bowen, notes that when the proposed Constitution was made public, “nothing created such an uproar as the lack of a bill of rights.” Yet, Bowen observes that “no delegate had been against such rights.” So why was a bill of rights omitted? Or as David Stewart asks in The Summer of 1787, “How could the leaders of the Revolution, having fought the British to vindicate American liberty, forget to include those rights in the Constitution?”

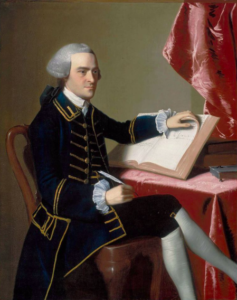

The Constitutional Convention began on May 25, 1787. On August 20th, more than three-quarters of the way through the long, hot summer, Charles Pinckney of South Carolina proposed adding several protections for individual rights. Pinckney’s suggestions to the Committee on Detail included protecting “liberty of the press” and a ban on the quartering of soldiers in private homes. While the Committee did not disagree with the importance of the underlying rights, all of Pinckney’s recommendations were rejected. As a result, Pinckney’s proposal did not reach the Convention floor.

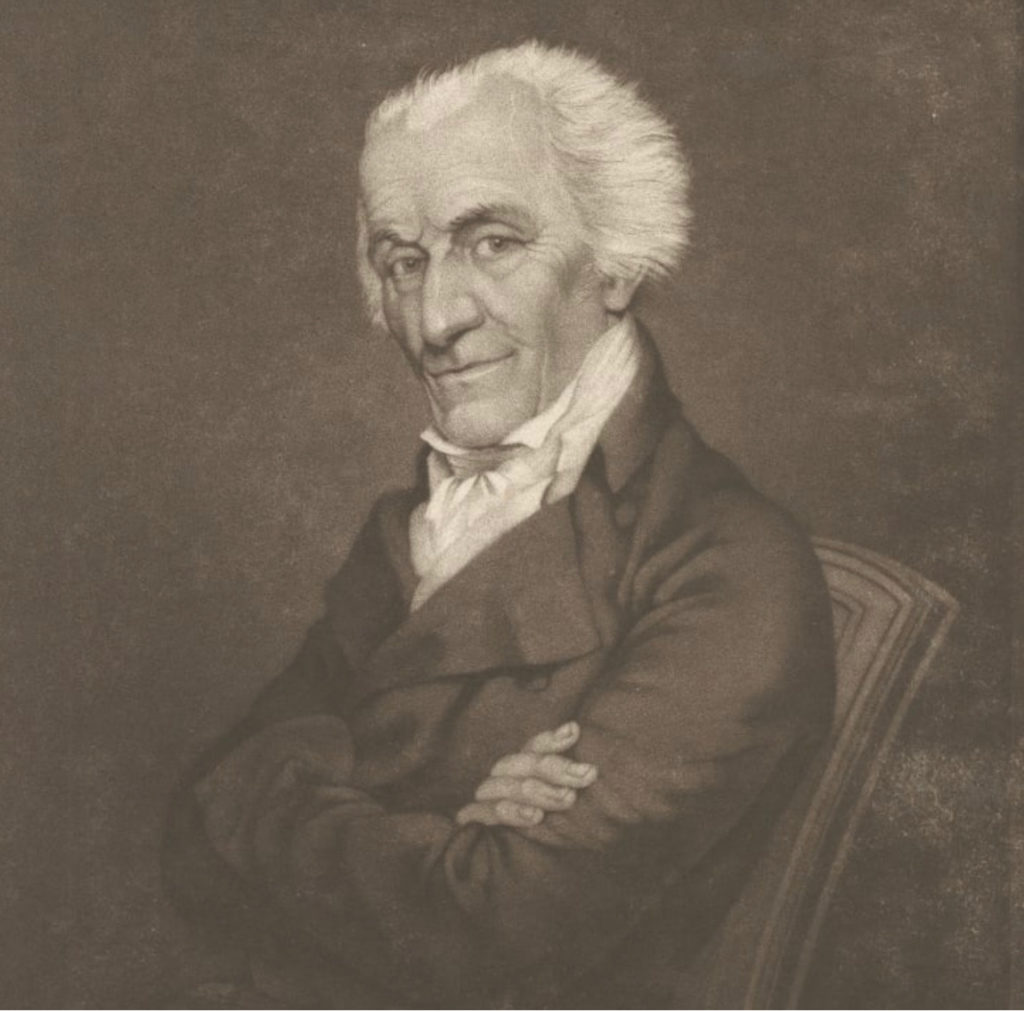

On September 12, five days before the end of the Convention, Eldridge Gerry of Massachusetts proposed that the right to a jury in civil cases should be guaranteed by the Constitution. After this proposal was rejected, George Mason of Virginia seized the opportunity to propose that the Constitution be “prefaced with a Bill of Rights.” Mason, the principal author of the Virginia Declaration of Rights, offered that a bill of rights could be modeled after previous state declarations. Mason suggested that a declaration could be prepared in only a few hours, which he volunteered to do.

According to Madison’s notes on the Convention:

[Colonel Mason] wished the plan had been prefaced with a Bill of Rights…It would give great quiet to the people; and with aid of the State declarations, a bill might be prepared in a few hours.

Agreeing with Mason, Eldridge Gerry of Massachusetts made a formal motion to proceed with a bill of rights. Mason seconded the motion. During a brief debate, Roger Sherman of Connecticut explained that, “[t]he state declarations of rights are not repealed by this Constitution, and, being in force, are sufficient.” Concerned that federal supremacy would render the states bills of rights insufficient, Mason responded that the laws of the United States “would be paramount to state bills of rights.” Nevertheless, all ten of the states delegations present unanimously voted against Gerry’s motion. Interestingly, Massachusetts was absent for the 10 to 0 vote. Historian Catherine Bowen speculates that Gerry must have left the Chamber.

When the Gerry/Morris motion to add a Bill of Rights was voted down, the Committee on Style had already delivered the final draft of the Constitution. Gouverneur Morris was working on the cover letter to the Confederation Congress that would deliver the product of four months of intense labor. Had Mason’s proposal for a Bill of Rights been approved, it arguably would have had to travel back through the Committee on Style.

Why was the Gerry/Morris motion was defeated? It was late into the drawn-out summer. Many founders claimed that a Bill of Rights was unnecessary. It is also likely that the Gerry/Morris motion could have been deemed a delaying tactic. Joseph Ellis in The Quartet explains that the delegates’ reasons may have been more straightforward:

One could invent many elaborate reasons for the absence of a bill of rights…but the real reason was that the delegates in Philadelphia were thoroughly exhausted after a summer of intense debates, and by September they wanted to go home.

In other words, the framers probably feared that a debate over a Bill of Rights would prolong the Convention, or worse, risk the delicate and painstaking compromises that had been carefully crafted over the long, hot summer of 1787.

Two days later, on September 14, Gerry made one final effort to protect individual liberties. Once again the proposal was unanimously rejected. Gerry and Pinckney then proposed that “the liberty of the Press should be inviolably observed.” Roger Sherman replied that this was unnecessary as “[t]he power of Congress does not extend to the Press.” The majority of state delegations agreed with Sherman and voted down the “liberty of the Press” proposal.

As a result, the Constitution guaranteed only a handful of specific rights: the writ of habeas corpus was preserved by Article I, Section 9; laws impairing the obligation of contracts, ex post facto laws and bills of attainder were prohibited by Art. I, Section 10. Article III guaranteed jury trials in criminal cases and required two witnesses plus an overt act to be convicted of treason. Article VI prohibited religious tests as a qualification for office.

On September 15, the next-to-last day of the Convention, three delegates explained their reasons why they could not sign the Constitution. For George Mason, Eldridge Gerry and Edmund Randolph, the absence of a bill of rights was a key objection. The Constitution was signed on September 17th by 39 delegates, with Mason, Gerry and Randolph advocating for a second convention.

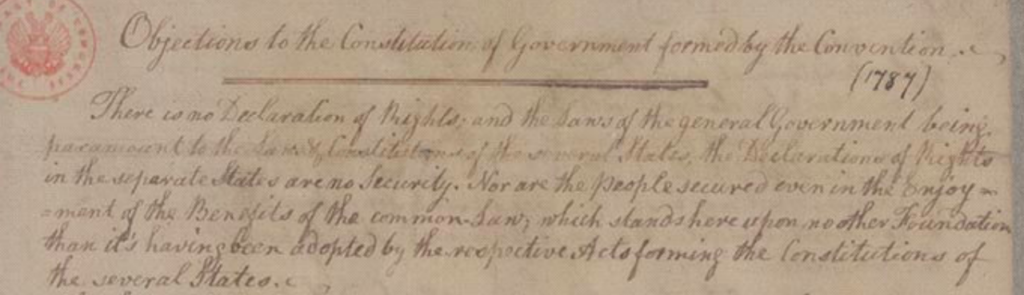

As one of the leading Anti-Federalists, Mason published his influential Objections to the Constitution of Government Formed by the Convention. The opening line of Mason’s Objections explained his opposition and reasons for not signing the Constitution:

There is no Declaration of Rights; and the Laws of the general Government being paramount to the Laws & Constitution of the several States, the Declarations of Rights in the separate States are no Security.

During the Virginia ratification Convention in 1788, George Mason warned that without a bill of rights, “many valuable and important rights would be concluded to be given up by implication.” For Mason, “unless there were a bill of rights, implication might swallow up all our rights.”

Mason’s credentials were impressive. In 1774, he had authored the Fairfax Resolves, which gave voice to the Revolution and was delivered by George Washington and Patrick Henry to the First Continental Congress. Two years later, Mason was the principal author of the Virginia Declaration of Rights, which served as a model for Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence. In 1785, Mason’s compact between Maryland and Virginia was an early first step on the road to the Constitutional Convention.

Other Anti-Federalist publications included Hon. Mr. Gerry’s Objections, which went through 46 printings. Not surprisingly, Elbridge Gerry focused on the lack of a bill of rights. The eighteen so called Letters from the Federal Farmer has been attributed to Anti-Federalist Richard Henry Lee of Virginia, or Melancton Smith of New York. George Clinton wrote under the pseudonym Cato. Other famous Anti-Federalists included Patrick Henry, Thomas Paine, Sam Adams, and Mary Otis Warren, the author of the pamphlet, Observations on the new Constitution, and on the Federal and State Conventions written under the pseudonym “A Columbian Patriot”, also advocated the addition of a Bill of Rights.

Arguments over a Bill of Rights

The first skirmish over a bill of rights occurred in September of 1787 in New York at the soon-to-be-obsolete Confederation Congress. Anti-Federalist Richard Henry Lee and Melancton Smith moved to add a bill of rights to the pending Constitution before it was sent to the states. Madison successfully opposed the motion on procedural grounds by focusing on the practical complications that would be presented if the Confederation Congress added its own proposals to the deliberative product drafted by the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia.

There are several reasons why Madison and most Federalists opposed a bill of rights. They argued that it was 1) unnecessary, 2) redundant, 3) useless, 4) potentially dangerous, and 5) a violation of the principles of republican government.

Madison joined Alexander Hamilton in drafting the Federalist papers in November of 1787. In Federalist 48, Madison explained that he didn’t place much trust in enumerations of rights, or in any other mere “parchment barriers” to government encroachments on liberty. Rather, Madison and the Federalists relied on the structural protections built into the Constitution: separation of powers, checks and balances, and the enumerated of limited Congressional powers. For Madison, “experience proves the inefficacy of a bill of rights on those occasions when it is most needed.” Madison noted in correspondence with Jefferson that “Repeated violations of these parchment barriers have been committed by overbearing majorities in every state.”

In Federalist 84, Hamilton argued that that “the constitution is itself in every rational sense, and to every useful purpose, a bill of rights.” Hamilton argued that:

bills of rights are, in their origin, stipulations between kings and their subjects, abridgements of prerogative in favor of privilege, reservations of rights not surrendered to the prince. Such was the MAGNA CHARTA, obtained by the barons, sword in hand, from King John.

For Hamilton, bills of rights had no application to a Constitution “founded upon the power of the people, and executed by their immediate representatives and servants.” Hamilton argued that in a constitutional republic, “the people surrender nothing; and as they retain every thing they have no need of particular reservations.” Hamilton then proceeded to quote the preamble that “WE, THE PEOPLE of the United States, to secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity, do ORDAIN and ESTABLISH this Constitution for the United States of America.”

Oliver Ellsworth, writing under the pseudonym “Landowner” took the position that the theory of the constitution itself precluded the need for a bill of rights. For Ellsworth, a bill of rights would be “insignificant since the government is considered as originating from the people, and all of the power of government now has is a grant from the people.”

Roger Sherman agreed that a bill of rights was overrated by Mason. Writing as “Countryman“, Roger Sherman explained that “the only real security” for important rights “must be in the nature of your government.” Employing his sharp wit, Sherman wrote:

No bill of rights ever yet bound the supreme power longer than the honey moon of a new married couple, unless the rulers were interested in preserving the rights; and in that case they have always been ready enough to declare the rights and to preserve them when they were declared.

For many Federalists a bill of rights was unnecessary because states were the main guarantors of liberty. Moreover, in their mind, the federal government lacked the power to interfere with the basic rights that would be protected by a bill of rights. In Federalist 38 Madison asked rhetorically whether a bill of rights was really essential to liberty the Articles of Confederation “has no bill of rights.” Of course, Madison’s comparison to the Articles of Confederation is slightly disingenuous where the new Constitution envisioned a substantially more muscular federal government.

Pennsylvania became the first large state to ratify the Constitution in December of 1787. It was the second state to ratify, following less than a week behind Delaware. Benjamin Rush argued at the Pennsylvania convention that he “considered it an honor to the late convention that this system has not been disgraced with a bill of rights. Would it not be absurd to frame a formal declaration that our natural rights are acquired from ourselves?”

James Wilson of Pennsylvania reasoned that the act of enumerating the rights of the people would have been dangerous, because it would imply that rights not explicitly mentioned did not exist. Hamilton echoed Wilson’s point in Federalist 84.

Madison worried that an incomplete list of rights would do more harm than good. Madison had good reason for concern. He believed “that a positive declaration of some of the most essential rights could not be obtained.” In particular, Madison feared that New England states would “narrow” rights of conscience and weaken any attempt to require separation of church and state.

Writing from New York on October 17, 1788, Madison spelled out his reasoning to Thomas Jefferson:

because there is great reason to fear that a positive declaration of some of the most essential rights could not be obtained in the requisite latitude. I am sure that the rights of Conscience in particular, if submitted to public definition would be narrowed much more than they are likely ever to be by an assumed power. One of the objections in New England was that the Constitution by prohibiting religious tests opened a door for Jews Turks & infidels.

In South Carolina, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney delivered a disturbing (but brutally honest) reason to avoid drafting a bill of rights. Described by historian Catherine Bowen as the “nakedest statement of all,” Pinckney explained that bills of rights “generally begin with declaring that all mean are by nature born free. Now, we should make that declaration with a very bad grace, when a large part of our property consists in men who are actually born slaves.”

Historian Joseph Ellis explains the political context of why the Federalists resisted a Bill of Rights. Two of the most powerful Anti-Federalists, New York Governor George Clinton, and former Virginia Governor, Patrick Henry, were calling for a second convention. Madison feared that a second convention would to seek to weaken federal power and undermine the delicate compromises reached at the Philadelphia Convention. According to Ellis:

Madison’s motives were primarily political. Madison saw the bill of rights as a political tactic to undermine Anti-federalists such as George Clinton and Patrick Henry, who were pushing for a second convention, “which Madison regarded as a thinly veiled attempt to undo” what had been accomplished in Philadelphia

Historian Gordon Woods also explains:

Because the Federalists believed that the frenzied advocacy of a bill of rights by the Anti-Federalists masked a basic desire to dilute the power of the national government, they were determined to resist all efforts to add amendments.

Madison was intimately familiar with the intensity of Anti-Federalist opposition, which was particularly strong in the large states of Virginia, Massachusetts and New York. Madison was rightly concerned that a second convention would reopen the entire Constitution framework to reconsideration. Having served as the recorder of the Constitutional Convention, Madison recognized the poor odds of repeating its success.

Madison wrote to Jefferson that he feared that there would be “little” of the “same spirit of compromise” from the summer. He no doubt agreed with Charles Coteworth Pinckney’s observation during the closing debate in Philadelphia that “Conventions are serious things and ought not to be repeated.” As described in Part III (pending), Madison understood that navigating the amendment process would be more manageable during the first Congress, rather than taking the risks of a runaway second convention.

Massachusetts Compromise:

The Massachusetts Convention began in January 1788 with an Anti-Federalist majority seemingly prepared to reject ratification. John Hancock, an apparent Anti-Federalist, was elected to preside over the convention. The old revolutionary, Sam Adams, had been committed to individual rights for decades. The Massachusetts Federalists suggested a compromise that would set an important precedent that would be followed by Federalist and Anti-Federalist alike.

John Hancock was persuaded to present the proposed amendments to the Convention. Samuel Adams offered a counter-proposal that the convention add a bill of rights to the beginning of the Constitution and ratify both. The danger of Adams’ proposal, however, was that ratification by Massachusetts would have been conditional and would only have gone into effect if other states agreed to the Massachusetts amendments.

After Adams’ motion failed, he helped Hancock negotiate the critical compromise. Adams agreed to join Hancock and support ratification, based on the assurance that nine recommended amendments would be adopted. With the endorsement of Hancock and Adams Massachusetts became the sixth state to ratify. On February 6, 1788, a handful of other Anti-Federalists joined with Hancock and Adams and the Constitution narrowly passed 187 to 168.

Of the remaining states to subsequently vote for ratification, four followed the Massachusetts model of recommending amendments as part of the ratification process. New York proposed 31 amendments, North Carolina 26, and Virginia 40.

Virginia Ratification Convention:

In March of 1788 Madison departed New York for Virginia to lead the Federalist drive for ratification in his home state. For the first time in his career Madison was forced to campaign for office. Although he defeated his closest Anti-Federalist rival by a margin of nearly 4-1, the Virginia Convention would be divided nearly evenly between Federalists and Anti-Federalists.

Madison knew that the Anti-Federalist opposition led by Patrick Henry would be formidable. Madison divided the Anti-Federalists into two camps: those who “do not object to the substance of the Governt. but contend for a few additional Guards in favor of the Rights of the States and the people” and others who sought amendments intended to “strike as the essence of the System.” Madison placed Edmund Randolph and George Mason in the first category. The second camp was led by Patrick Henry who Madison believed had “disunion assuredly for its object.”

Madison also understood that many Anti-Federalists were not truly interested in a Bill of Rights, but were only interested in stopping ratification. For these demagogues, the call for a bill of rights was a useful smokescreen.

In opposing ratification in 1788 Patrick Henry demanded a bill of rights, but he would subsequently attempt to use his political power to stop Virginia from ratifying the Bill of Rights in 1791. Henry correctly understood that once the Bill of Rights was ratified there would be little chance that a second convention would be called to rewrite the Constitution. Tench Coxe, a leading Federalist from Philadelphia, observed that “honest” Anti-federalists supported the Bill of Rights. Of course, Coxe was implying that some Anti-Federalists used the demand for a bill of rights as a smokescreen for their opposition. Letter from Tench Coxe to James Madison.

In a letter dated April 22, 1788 to Thomas Jefferson, Madison provided his assessment of the pending ratification struggle in Virginia between “friends” and “enemies” of the Constitution. Madison explained his concern that the amendment process could be used as a “mask” for those favoring “disunion.”

if a second Convention should be formed, it is as little to be expected that the same spirit of compromise will prevail in it as produced an amicable result to the first. It will be easy also for those who have latent views of disunion, to carry them on under the mask of contending for alterations popular in some but inadmissible in other parts of the U. States.

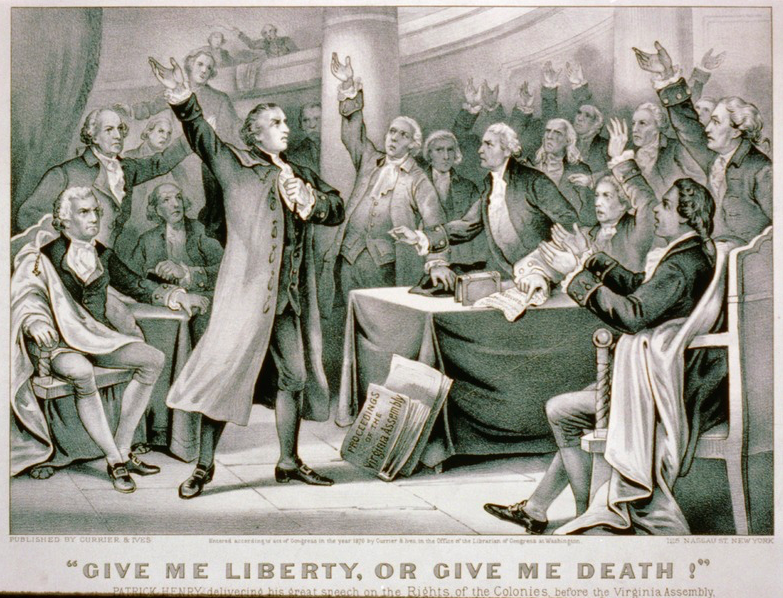

Anti-Federalist Patrick Henry was a five term governor of Virginia. A renown orator famous for his “Give me Liberty or Give Me Death Speech!,” Henry’s reputation and stature was exceeded only by George Washington. Patrick Henry refused to attend the Constitutional Convention because he “smelt a rat.”

Henry’s goal was to force a second constitutional convention which would not only adopt a “Bill of Rights”, but would also severely limit federal power. In particular, Henry and many other Anti-federalists opposed direct taxation, federal supremacy, and the wide ranging powers granted to the federal judiciary.

Madison’s strategy going into the Convention played upon his strengths. Facing a fiery orator like Patrick Henry, Madison relied on his logical reasoning and knowledge of the proposed Constitution. Madison spoke more than any other Federalist at the Virginia Convention. As a seasoned debater Madison’s tone was always conciliatory and respectful, which helped win over undecided delegates. In a June 6 speech, Madison systematically exposed Patrick Henry’s inaccurate reading of history, flawed logic and misapplication of the proposed Constitution.

Patrick Henry asserted that a bill of rights was “indispensably necessary” and should include “a general positive provision…securing to the States and the people, every right which was not conceded to the General Government.” This would later become the 9th and 10th Amendments. Not conceding to the Massachusetts compromise, Henry pointed to “the absurdity of adopting this system, and relying on the chance of getting its amendments afterward.” Henry compared the “ratification first” “amend later” approach to being bound hand and foot for the sake of being unbound. You don’t enter a dungeon, for the same of getting out. For Henry, this compromise procedure was contrary to “human nature,” which Henry asserted would “never part with power.”

Edmond Randolph who had refused to sign the Constitution in Philadelphia spoke in favor of his change in position to support ratification. After eight states ratified the Constitution, Randolph concluded that Virginia could not expect amendment to precede implementation, whatever it might do. If Virginia insisted on prior amendments it would lose it influence and would have little input in drafting the amendments. Randolph did not need to spell out the fact that if Virginia did not ratify, its preferred candidate, George Washington would not be able to serve as President. Randolph, George Washington’s personal attorney, would be appointed by Washington to serve as the first Attorney General the following year.

At the Virginia ratification convention, a committee led by law professor George Wythe drafted forty recommended amendments for Congress. Twenty of the proposals enumerated individual rights and another twenty addressed states’ rights.

Following Massachusetts’ lead, the Federalists in both Virginia (led by Madison) and New York (led by Hamilton) were able to narrowly achieve ratification linked to recommended amendments and a Bill of Rights. Virginia voted 89 – 79 on June 25. New York followed suit on July 26 with a 30 – 27 vote. Madison and Hamilton purposely delayed the ratification votes in their home states so that momentum in the early states would work to their favor. And it did.

Part III (pending) continues the story as Madison champions the adoption of a Bill of Rights at the First Congress.

Additional reading:

Pauline Maier, Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787-1788

Richard Labunski, James Madison and the Struggle for the Bill of Rights

Catherine Drinker Bowen, Miracle at Philadelphia: The Story of the Constitutional Convention (1966)

James Madison and the Federal Constitutional Convention (National Archives)

Ratification Timeline and Publications (TeachingAmericanHistory.org)

What Would the Founders Think blog

Bill of Rights timeline (TeachingAmericanHistory.org)

Kevin Gutzman, James Madison and the Making of America (2012)

Andrew Bernstein and Nancy Isenberg, Madison and Jefferson (2010)