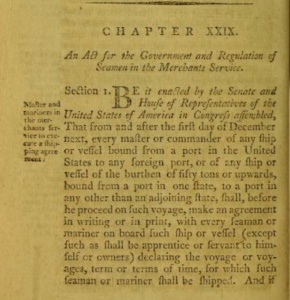

Act for the Government and Regulation of Seamen

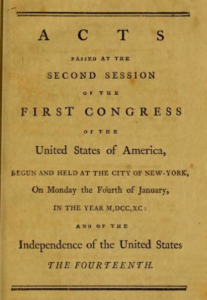

[First Congress, 2nd Session, Ch. 29; 1 Stat. 131; July 20, 1790]

While not widely known, the first federal labor law was adopted by none other than the first Congress in 1790. The “Act for the Government and Regulation of Seamen” represented a robust effort to protect the rights of sailors, who had historically been subject to exploitation by ship owners (and/or ship “masters”). The Act was premised on a compromise between labor and management: in exchange for enforceable contractual rights and workplace safety protections, sailors agreed not to desert their ship until the expiration of their specified contract term.

The Act contains nine sections which provide as follows:

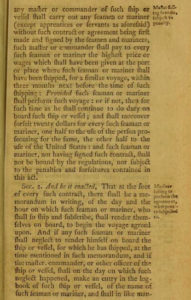

[E]very master or commander of any ship or vessel bound from a port in the United States to any foreign port…shall, before he proceed on such voyage, make an agreement in writing or in print, with every seaman or mariner on board such ship or vessel (except such as shall be apprentice or servant to himself or owners) declaring the voyage or voyages, term or terms of time, for which such seaman or mariner shall be shipped.

If a ship captain violated the Act and did not memorialize the agreed wages in writing, the owner was obligated to pay to “every such seaman or mariner the highest price or wages which shall have been given at the port or place where such seaman or mariner shall have been shipped, for a similar voyage, within three months next before the time of such shipping.”

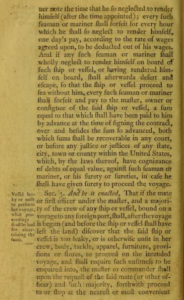

Section 3 allows crew to demand that unseaworthy ships proceed to the closest port where an inquiry can be made “and thereupon such judge or justice is hereby authorized and required to issue his precept directed to three persons in the neighbourhood, the most skilful in maritime affairs that can be procured, requiring them to repair on board such ship or vessel, and to examine the same in respect to the defects and insufficiencies complained of, and to make report to him the said judge or justice…” If it was determined that the complaint was without foundation, reasonable damages were payable by the complaining seamen from their wages.

Section 6 requires payment of 1/3 of a seaman’s wages due at every port, unless the parties had agreed otherwise. Section 7 contains anti-desertion protections and penalties, including arrest and jail until the ship is ready to depart.

Section 8 provided that every American owned ship weighing 150 or more tons, with ten or more crew, was required to contain customary medical supplies (known as the “medicine chest”):

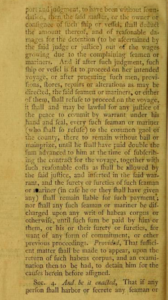

[E]very ship or vessel belonging to a citizen or citizens of the United States…shall be provided with a chest of medicines, put up by some apothecary of known reputation, and accompanied by directions for administering the same; and the said medicines shall be examined by the same or some other apothecary, once at least in every year, and supplied with fresh medicines in the place of such as shall have been used or spoiled; and in default of having such medicine chest so provided, and kept fit for use, the master or commander of such ship or vessel shall provide and pay for all such advice, medicine, or attendance of physicians, as any of the crew shall stand in need of in case of sickness, at every port or place where the ship or vessel may touch or trade at during the voyage, without any deduction from the wages of such sick seaman or mariner.

Section 9 regulated the supplies and food that were required for trans-Atlantic voyages:

That every ship or vessel, belonging as aforesaid, bound on a voyage across the Atlantic ocean, shall, at the time of leaving the last port from whence she sails, have on board, well secured under deck, at least sixty gallons of water, one hundred pounds of wholesome ship-bread for every person on board such ship or vessel, over and besides such other provisions, stores and live-stock as shall by the master or passengers be put on board, and in like proportion for shorter or longer voyages.

The Act involved an expansive application by Congress of its commerce power that would not be seen again until the growth of federal authority during the New Deal. According to legal historian David Currie, “[p]ossibly the most ambitious exercise of the commerce power during the First Congress was the enactment in July 1790 of a comprehensive labor law for merchant seamen. On the one hand this Act provided stringent sanctions against sailors who deserted or failed to report and those who harbored them. On the other hand, it guaranteed crew members a written contract, prompt payment of wages, adequate medicines and provender, and the right to require a leaky vessel to put into port for repairs.” David P. Currie, The Constitution in Congress: Substantive Issues in the First Congress, 1789-1791, 61 Univ. Chicago Law Rev. 775 (1994).

The Act involved an expansive application by Congress of its commerce power that would not be seen again until the growth of federal authority during the New Deal. According to legal historian David Currie, “[p]ossibly the most ambitious exercise of the commerce power during the First Congress was the enactment in July 1790 of a comprehensive labor law for merchant seamen. On the one hand this Act provided stringent sanctions against sailors who deserted or failed to report and those who harbored them. On the other hand, it guaranteed crew members a written contract, prompt payment of wages, adequate medicines and provender, and the right to require a leaky vessel to put into port for repairs.” David P. Currie, The Constitution in Congress: Substantive Issues in the First Congress, 1789-1791, 61 Univ. Chicago Law Rev. 775 (1994).

In the early twentieth century, Congress attempted to grant similar employment rights to railroad workers. These initial efforts were held unconstitutional, however, by the United States Supreme Court during the Lochner era. For example, in Adair v. U.S., 208 U.S. 161 (1908) legislation which banned “yellow dog” contracts that prevented workers from joining labor unions was struck down. See also Railroad Retirement Board v. Alton, 295 U.S. 330 (1935)(striking down the Railroad Retirement Act of 1934 which sought to establish pensions for railroad workers engaged in interstate commerce). The Alton decision divided the Court with Justices Charles Evans Hughes, Louis Brandeis, Benjamin Cardozo and Harlan Fiske Stone dissenting. Ultimately, the Court circled back in 1937 to the reasoning of the First Congress that the Commerce Clause provided wide authority to regulate interstate commerce, even if not regulating commerce itself. Readers are referred to the “switch in time that saved nine,” when President Roosevelt proposed a bill to pack the court with more appointments during the Depression.

Admiralty law and “Shipping Articles”: Under British admiralty law, the written contract between the captain of a ship and the crew was known as the “Shipping Articles” or simply the “Articles” for short. The “Articles” were initially executed when sailors were hired and signed again upon the completion of a voyage. The obligation to memorialize the Shipping Articles into a formal written contract was mandated by Parliament in 1729 (2 Geo. II, c. 36). Click here for the British “Act for the Better Regulation and Government of Seamen in the Merchants Service.” The American Act in 1790 borrowed extensively from the British Act adopted 61 years earlier.

Admiralty law and “Shipping Articles”: Under British admiralty law, the written contract between the captain of a ship and the crew was known as the “Shipping Articles” or simply the “Articles” for short. The “Articles” were initially executed when sailors were hired and signed again upon the completion of a voyage. The obligation to memorialize the Shipping Articles into a formal written contract was mandated by Parliament in 1729 (2 Geo. II, c. 36). Click here for the British “Act for the Better Regulation and Government of Seamen in the Merchants Service.” The American Act in 1790 borrowed extensively from the British Act adopted 61 years earlier.

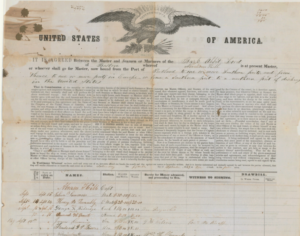

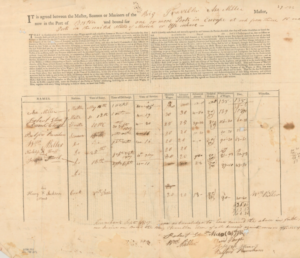

After the Act was adopted Customs Collectors distributed blank Articles at American ports. The form contracts were provided to ship captains and contained a copy of the 1790 Act. The printed copies quoted verbatim from the Act and indicated that the law was signed by President Washington, Secretary Jefferson and Speaker of the House Muhlenberg. Printed on the front of the Articles were the contractual provisions between the ship owner and the crew. Set forth below the contractual terms were columns for crew members’ signature (or mark), job description, place of birth, age, height, wages, hospital money, time of discharge, etc. “United States of America” was commonly printed at the top along with engravings of ships, eagles, or other maritime symbols. Every American-owned ship was required to maintain the original copy with the ships’ papers during the entire voyage. In the event of a dispute over payment of wages, the Articles were required to be produced as evidence to the justice of the peace or local magistrate. Execution of shipping articles was also required for fisherman, who were entitled to the same rights and obligations as sailors under the Act.

After the Act was adopted Customs Collectors distributed blank Articles at American ports. The form contracts were provided to ship captains and contained a copy of the 1790 Act. The printed copies quoted verbatim from the Act and indicated that the law was signed by President Washington, Secretary Jefferson and Speaker of the House Muhlenberg. Printed on the front of the Articles were the contractual provisions between the ship owner and the crew. Set forth below the contractual terms were columns for crew members’ signature (or mark), job description, place of birth, age, height, wages, hospital money, time of discharge, etc. “United States of America” was commonly printed at the top along with engravings of ships, eagles, or other maritime symbols. Every American-owned ship was required to maintain the original copy with the ships’ papers during the entire voyage. In the event of a dispute over payment of wages, the Articles were required to be produced as evidence to the justice of the peace or local magistrate. Execution of shipping articles was also required for fisherman, who were entitled to the same rights and obligations as sailors under the Act.

This obligation to formalize written employment contracts with sailors has remained a central component of U.S. maritime law for over two hundred years. To this day, federal admiralty law unequivocally provides that “[t]he owner charterer, managing operator, master, or individual in charge shall make a shipping agreement in writing with each seaman before the seaman commences employment.” Among other things, the written agreement must discuss: (1) wages, (2) the nature, and, as far as practicable, the duration of the intended voyage, and the port or country in which the voyage is to end; (3) the number and description of the crew and the capacity in which each seaman is to be engaged; (4) the time at which each seaman is to be on board to begin work; and (5) regulations about conduct, fines, and other punishment.

For a link to the current federal statute click here: 46 U.S.C. § 10302.

Additional contract requirements and formalities are specified in 46 U.S.C. § 10304 and can be traced back to the 1790 Act.

Here is a link to additional federal regulations governing Shipping Articles, 46 CFR 14.207.

Here is a link to the modern version of Shipping Articles (Coast Guard form) in use today.

Since new Articles were required for each voyage they are valuable and relatively reliable primary sources for historians, sociologists, economists, and other researchers. Ordinarily, the Articles contain the following information about the crew: names, ages, physical descriptions, job descriptions, wages, places of birth, places of residence, and ages. Accordingly, wage inflation, demographics and literacy can be tracked over time on the same ship. Shipping Articles are also highly collectible.

Background: Admiralty law has long recognized that ship owners/master have disproportionate bargaining power over sailors from the moment Articles are signed. Discipline for sailors often involved corporal punishment as was vividly depicted by Herman Melville in Billy Budd (1924) and White Jacket (1850). Melville’s books were informed by his personal experience during the late 183o’s and early 1840’s as a cabin boy on the St. Lawrence and as a common seaman aboard the frigate USS United States.

Arguably one the most problematic features of the Act was the consequences for sailors who deserted their ship. Section 7 of the 1790 Act provided that desertion was punishable by arrest and imprisonment with bounties being issued for “runaway” sailors. At times of high demand for sailors, “land sharks” (also know and “crimps”) were known to “recruit” drunk sailors without their full consent. Examples have been documented of crimps that were so eager to retain sailors that they would row out to meet incoming vessels.

Additional reading:

Click here for a link to John Adams’ copy of the Act, published in the Laws of the United States by Richard Folwell (1796)

The Seaman’s Friend A Treatise on Practical Seamanship, Richard Henry Dana (1851)

Mystic Seaport Museum in Mystic, Connecticut, contains an extensive and searchable online collection of maritime records: mysticseaport.org

Here are examples of Shipping Articles from 1805, 1809, 1825, 1831, 1849, 1851, 1860, digitized with funding by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

Copied below are pictures of the Act and examples of engravings or other illustrations used at the top of elaborate Shipping Articles.